Alexandrine Tinne (1835-1869) was the daughter of a wealthy merchant in 19th century The Hague. Her father left her a fortune so vast that she could spend it at will on as lavish a lifestyle as she desired. But instead of wasting her inheritance on elaborate dinner parties and other pastimes of ‘Haguois’ high society, she extensively travelled in Egypt, North Africa and the Near East. Her journeys would eventually bring her deep into the Sudan and to the deserts of Algeria and Tunisia.

Growing up in the large family home at Lange Voorhout 32, amidst the relics of her father’s travels, Alexine developed an interest in geography, history and photography. With the Royal Library next door, she never lacked reading material. As a child, she accompanied her father on his trips through Europe, and after his death she and her mother Henriëtte visited Scandinavia. Their wanderlust increased and in December 1955, after crossing the Mediterranean, mother and daughter first set foot on the African continent at the port of Alexandria.

In Cairo, while staying at the exclusive Shepheard’s Hotel, Alexine marvelled at the ‘Arabic way of life’ and decided to learn the language. As true tourists until the present day they visited the sights between Luxor and Aswan. Further excursions brought them to the Red Sea, Syria, Plaestine and Lebanon. By this time, Alexine longed to travel further up the Nile. In 1857 they embarked on a dahabiyah (a houseboat equipped with sails) to navigate in several weeks to the third cataract of the Nile at Wadi Halfa. After viewing the temples of Abu Simbel, the two returned to Cairo and eventually back to The Hague.

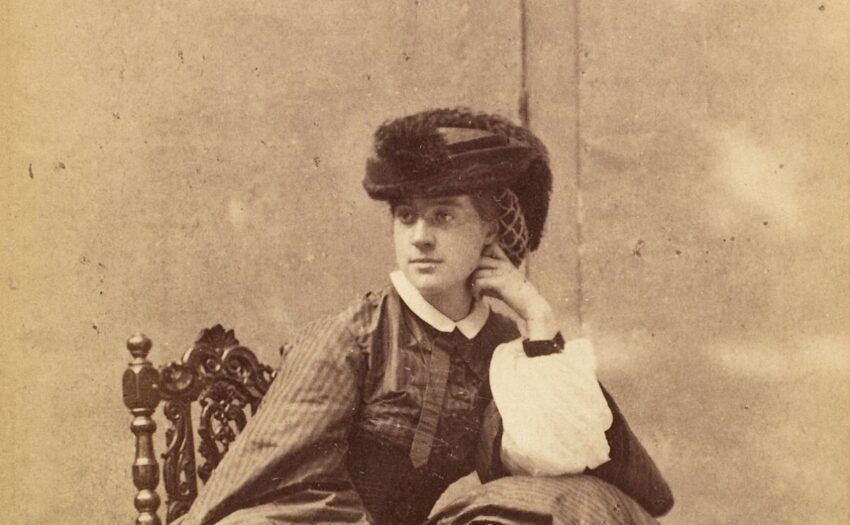

Alexine Tinne in The Hague

Alexine Tinne in The Hague

The virus had caught them now, and after several more trips through Europe, they returned indefinitely to Africa in 1861. This time, Alexine was set on exploring the Sudan. Up the Nile from Khartoum, the land became less a tourist destination, more an unknown territory with a potentially hostile environment. Several male explorers had treaded these regions, but never a Western woman. Speke and Grant were about to set out to find the source of the Nile, and Samuel Baker took his wife (bought on a slave market in Eastern Europe) on a similar course.

The White Nile

The three ladies (aunt Adriana had joined Henriëtte and Alexine) spent their winter at the Mena House Hotel in Giza, before they rented three boats that would bring them to Khartoum. In a letter home, Henriëtte gives an account of the cargo they were to carry all the way up the Nile and through the Nubian desert:

“One should bring everything along, so I took £800 with me in copper money. We have cargo for 10 camels, 40 water jars, six tents, iron bedsteads, matresses, weapons… Every item necessary to spend 18 days in a desert without water.”

As if this was insufficient, they brought 32 boxes of furniture, engravings, books and mirrors from The Hague, as gifts and means of exchange. Aunt ‘Addy’ was terrified about the trip and already imagined herself being locked up in a harem. She trembled watching Alexine arrange her collection of pistols, revolvers and carbines. In January 1862 they finally began their journey.

After sailing to Korosko, the party disembarked, to continue through the desert with a caravan of 102 camels. All the cargo had to be carried, including Alexine’s five dogs and the bedsteads that came in handy during overnight stays and afternoon naps. At Berber the party reembarked and sailed on to Khartoum. From there, they wanted to push on to Gondókoro, 1000 kilometers further south. Because the slave trade rendered the area dangerous, they contracted forty extra soldiers. Slave traders and disease would indeed become their two greatest problems on the way.

At Gebel Dinka, Alexine witnessed the horrors of the slave trade during an overnight razzia. She was shocked to learn that both Arabs and Europeans treated the slaves terribly. Nevertheless, when a slave woman appealed to her in order to be reunited with her mother and son, Alexine was touched and purchased the whole family. She bought several more slaves, including a little Abessynian girl. Along the way south Alexine spent some time catching exotic animals, was asked to marry a local Arabic merchant, and marvelled at ostriches, giraffes, elephants and hippos (most of which she wanted to try for dinner). When they finally reached Gondókoro, the whole company was felled by illness. They returned to Khartoum, concluding their trip on the While Nile.

The Gazelle river

In Khartoum, Alexine met the German ornithologist Theodor von Heuglin, who joined their party with two fellow companions. Together, they planned to explore the Bahr el-Ghazal river. This time they brought 60 soldiers, donkeys and plenty of gunpowder. In spite of this precaution, Alexine wrote in a letter home how she found the local population ‘a good kind of people, childlike and gullible, but very friendly and kindhearted’. Unlike the Europeans and traders she encountered:

“As soon as they are on the Nile, they consider themselves to be above and beyond every divine and human law. They plunder, kill and do whatever comes into their head.”

In 1863 they set out once again with a fleet consisting of a steamboat (rented at exorbitant rates from the son of the khedive), two large dahabiyah’s and three transport ships with soldiers and provisions. The entire expedition conisted of over 150 people. It would result in a cumbersome undertaking marred by heavy spring rains and consequent disease. Aunt Addy remained in Khartoum while the company sailed to Meshra el-Rek, where Alexine arrived as a ‘triumphant Cleopatra on the Nile’, according to an eye witness.

From there, they wanted to cross the Kosanga mountains to reach the legendary Azande people. Due to a miscalculation, however, they were short in supplies, and the rainy season was soon approaching. The Gazelle river turned out to be a large swamp. The expedition continued over land with the feverish Alexine on an improvised stretcher, mother Henriëtte in a sedan chair, and their maids Flore and Anna on donkeyback. 120 servants carried their hand baggage. Eventually they reached Wau, where they encountered Biselli, the local trader in slaves and ivory. Instead of bringing relief, he would make their lives more difficult and ask for increasingly high prices in exchange for his ‘hospitality’.

When first her mother Henriëtte and then her faithful maids Flore and Anna died of illness, Alexine returned to Khartoum defeated. She realised she could not return to Europe:

“It is not due to a romantic enthusiasm for the East, or because of excentricity, but from motives that you will understand, when you consider them. To return by myself, to an empty home… No, I cannot tell you how much I shudder at the idea – it would be an evil dream. Here I can live freely and peacefully, naturally without daily struggles. I feel relatively at home.”

African adventures

Staying in Africa she did. After the death of her aunt Addy and an official complaint by the local authorities that she had participated in slave trade, she moved to Berber, on to Suez and then to Cairo. Here she met her brother John and his wife Margaret, whose conservatism clashed with her excentric and stubborn personality. Alexine went about clad in Arabic attire, on donkeyback, and was full of ‘exotic ideas’ according to her sister-in-law. She wanted to buy a house in Cairo but could not find a place to settle. Eventually she rented a yacht, sailed around the Mediterranean for a while, and came up with a new plan: to traverse the Algerian desert towards the land of the Tuareg.

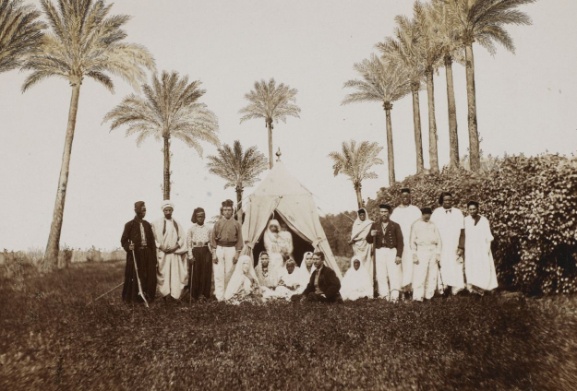

Alexine’s entourage (Alexine is possibly the veiled woman)

Alexine’s entourage (Alexine is possibly the veiled woman)

Alexine was unstoppable, and led two further expeditions into North Africa. Her entourage consisted of a strange mixture of ransomed slaves and a ship’s crew. On photos made at the time, Alexine sometimes featured completely veiled. The second trip, through the desert of Tunisia, proved fatal to her. In a confusing incident, concerning a row between Arabs and Tuareg, Alexine was accidentally or deliberately stabbed to death. Her belt was found back later by her brother John on the market of Ghat. Before her final expedition, Alexine wrote:

“I never understood the joy of growing older. I have always found it sad – even under the merriest of circumstances – and I find the thought of dying happily and brave, by a knife or gunshot, not terrible…”

Alexine was both extravagant and pragmatic. Extravagant in the amounts of money she spent and the plans she made to enter deep into unknown territory as one of the first Western women in history. Empty spaces on the map of Africa intrigued her as much as it did her male counterparts. She was pragmatic in the way she went about preparing for her journeys without sense of danger: by collecting heaps of baggage and a large entourage, and literally seeing where the ship would run aground. She was not studious, wrote little letters and could not care to keep a diary. Most of what we know about her travels comes from letters written by those around her.

The letters paint a character of Alexine that is both impressive and naive. Having no father, husband or lack of funds to keep her back, she could move around in the world freely and to her heart’s content. The family members and servants she dragged with her on her travels were, however reluctant, even more reluctant to leave her side, which eventually led to many a tragic death far from home. Home for her was on the road, or preparing for a new adventure. In this way, although she never settled, everywhere she went in the world Alexine created a home for herself.

Read more (in Dutch):

Beek, N. van de, De wonderbaarlijke reizen van Alexine Tinne, Phoenix 64/3 (2018), 35-47.

Hi Nicky

I’m a PhD student from Australia in the Hague to look at the sketchbooks of Alexine Tinne at the Historic Museum. I found your post whilst looking for her address. Alexine left no diary, so it should be interesting to see what her sketchbooks reveal of her thinking. Thanks for your post

cheers

Annie

Hi there,

There is one picture in the internet with Alexandrine Tinné sitting on a camel and holding a flag. Do you know what flag this is?

Best regards

Reinhold