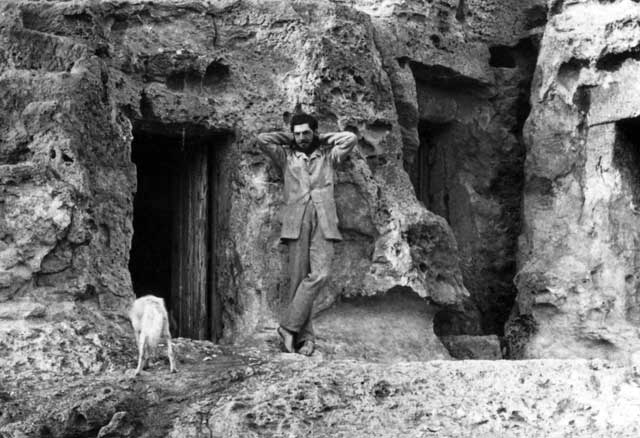

When the Englishman William Flinders Petrie (1853-1942) first came to Egypt, he was 27 years old. Visitors to the Giza plateau must have looked up in suprise when they noticed a young man in pink pyjamas emerging from one of the rock tombs in the morning. In the desert glare it almost seemed as if the apparition was naked, so Petrie was usually left alone during his work.

Coming from a family of travellers and researchers, Petrie had a knack for history and foreign languages since childhood. As a home-schooled boy of ill health, his mother taught him languages while his father took him surveying in the environment of Kent. Aged fifteen, he first visited the British Museum in London and was intrigued by its Egyptian collection. Closer to home, the English prehistoric landscape was subject of investigation, and at nineteen, Petrie undertook a study of the geometry of Stonehenge.

Petrie came to Giza in the winter of 1880 armed with measuring instruments to perform a similar study of the principal pyramids. He was struck by the rate of destruction of ancient monuments and artefacts, and described the country as ‘a house on fire’. He made it his goal to salvage what was possible, with the intention of sitting down at sixty to record his findings.

A portrait of the artist…

A portrait of the artist…

Funded research

Back in England, Petrie met wealthy traveller and writer Amelia Edwards, well-known for her travelogue A Thousand Miles Up The Nile. She established the Egyptian Exploration Fund (now Society) in 1882 with Petrie as its protagonist. He left with a bag of money for Tanis in the delta, where he carried out a meticulous excavation, making careful notes and recording the sightest details. Here, he uncovered the temple of Psusennes I. Cutting out the middle man, he himself took control over the site, directing a workforce of 170 men.

In 1887, Petrie was fed up trying to please the London society with his work in Egypt, and resigned. Together with Francis Llewelyn Griffith (of the later Griffith Institute), he travelled up the Nile and took hundreds of photographs. Photography was the new medium that would greatly enhance archaeological research. At Medinet Habu, Petrie took casts of the temple walls.

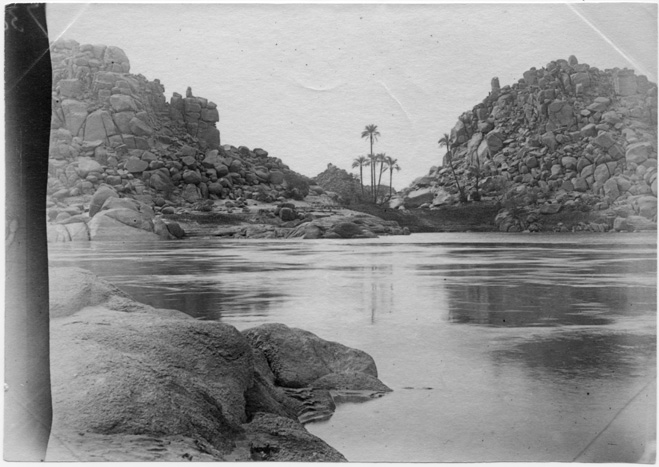

They reached Sehel at the First Cataract, Egypt’s classic border with Nubia. Here, numerous inscriptions adorned the rock walls, recording southern campaigns and the travels of high officials. The Famine Stela describes how king Djoser in desperation brought offerings to the gods of the Nile. Carrying rope ladders and drawing supplies, the gentlemen went to work each day to make sketchings and engravings.

The island of Biga near Aswan (photo by Petrie)

The island of Biga near Aswan (photo by Petrie)

The Fayum

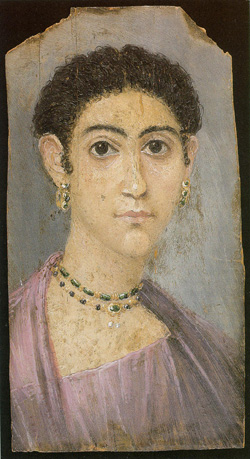

A telegram arrived from Edwards, anouncing that Petrie would again receive a bag of money to work in the Fayum oasis. There, at the pyramid site of Hawara, he disovered mummies from the first century BCE. Intriguingly, the mummies contained beautiful, life-like portraits placed over their faces. These mummies with their so-called Fayum portraits proved that during the Greco-Roman period, people kept their dead with them for a certain period of time, before being buried. The portraits were probably painted from life.

Petrie found about 60 portraits, which were traditionally divided up between the Egyptian Antiquities Service and the British team. Petrie was appalled when he found out that the beautiful portraits had been left lying in the rain outside the Cairo museum. Egypt chose twelve portraits, while 2/3 of the find went home with Petrie. They were exhibited in the newly established Egyptian Hall at Picadilly Square, Londen.

Petrie found about 60 portraits, which were traditionally divided up between the Egyptian Antiquities Service and the British team. Petrie was appalled when he found out that the beautiful portraits had been left lying in the rain outside the Cairo museum. Egypt chose twelve portraits, while 2/3 of the find went home with Petrie. They were exhibited in the newly established Egyptian Hall at Picadilly Square, Londen.

Continuing his research in the Fayum, Petrie excavated a working village near El-Lahun, where he uncovered many artefacts of daily use: flint and wooden tools, toys, clothing, weaving supplies and leather sandals. With his meticulous methods and detailed accounts, Petrie became the ‘archaeologist of daily life’, publishing a book every year about his findings.

Great discoveries

At Amarna, he excavated the palace of king Akhenaten in 1891. Here he discovered a splendid painted tile floor of 90 m2, showing an abundance of lotus flowers, fish, plants, cattle and water fowl. Petrie concurred that this was the most important find in his career. Unfortunately, when more and more tourists started coming to Egypt, often trampling the fields to arrive at archaeological sites, a local farmer in his fury destroyed the floor with a hammer. Thankfully, Petrie had made detailed drawings of the decoration, but a greater loss of Amarna art is hardly imaginable.

Natural motifs at Amarna

Natural motifs at Amarna

In 1892, both Petrie’s mother and his benefactor Amelia Edwards died. The latter donated her private Egyptian collection to the UCL and installed a chair by testament that was to be filled by Petrie. From now on, Petrie would spend each winter in his beloved desert, giving lectures during the rest of the year.

At Naqada, he excavated thousands of tombs from a formative period in Egyptian history, the fourth millenium BCE. Most of the tombs contained only skeletons and some pottery. In order to relatively date the tombs and describe their development, Petrie invented Sequence Dating, which we now call seriation. Thus, he distinguished between three main types of pottery, with changing decoration (from cross-lined in Naqada I, to figurative in Naqada II and rope decoration in the Late Predynastic period). Many examples of these types can be admired in the wonderful Petrie Museum in London.

In 1896, Petrie married his soulmate Hilda Urlin, who would accompany him for the rest of his life and assist at many an excavation. At Abydos, he uncovered the tombs of four kings and a queen, plus their high officials from the first dynasty. He carefully excavated the site according to its stratigraphy. Hilda worked alongside Petrie as a member of the team, besides taking care of the children and working out the field notes. Until his retirement in 1933, Petrie undertook more excavations in Egypt than anyone who has ever come before or after him.

Sir and Lady Petrie in Syria in 1934

Sir and Lady Petrie in Syria in 1934

Petrie projects

The Artefacts of Excavation project by UCL and the University of Oxford is currently trying to locate finds that were distributed from British excavations in Egypt between 1880 and 1980. Likewise, the Petrie Perspective project by the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam is focused on objects from Petrie’s excavations in Egypt between 1880 and 1920. Parts of the collection have ended up in the Netherlands and Germany, but some objects even found their way to Kyoto! These projects can give an interesting view of the workings of museums and excavations during on of the most fruitful periods of Egyptian archaeology.