Every Egyptologist is probably familiar with the sonnet ‘Ozymandias’ written by Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1818:

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert… Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

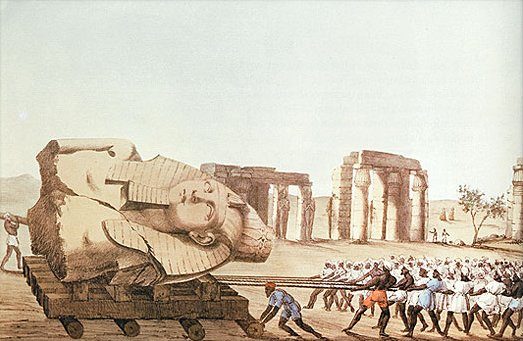

The poem recalls the greatness of king Ramesses II and the Egyptian empire, and its inevitable decline. It is likely that the torso just acquired by (but not yet arrived at) the British Museum from Belzoni’s wreaking havoc in the Ramesseum served as inspiration for the poem. ‘Ozymandias’ was a Greek rendering of the throne name of Ramesses II: User-maat-re Setep-en-re. The inscription on the base of the statue was rendered by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus as “King of Kings am I, Ozymandias. If anyone would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works.”

In fact, the sonnet was written in contest with poetic colleague Horace Smith, who wrote his own version:

In Egypt’s sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desert knows:—

“I am great Ozymandias,” saith the stone,

“The king of kings: this mighty City shows

“The wonders of my hand.” —The City’s gone!

Nought but the Leg remaining to disclose

The site of that forgotten Babylon.

We wonder—and some hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro’ the wilderness,

Where London stood, holding the wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful, but unrecorded race,

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

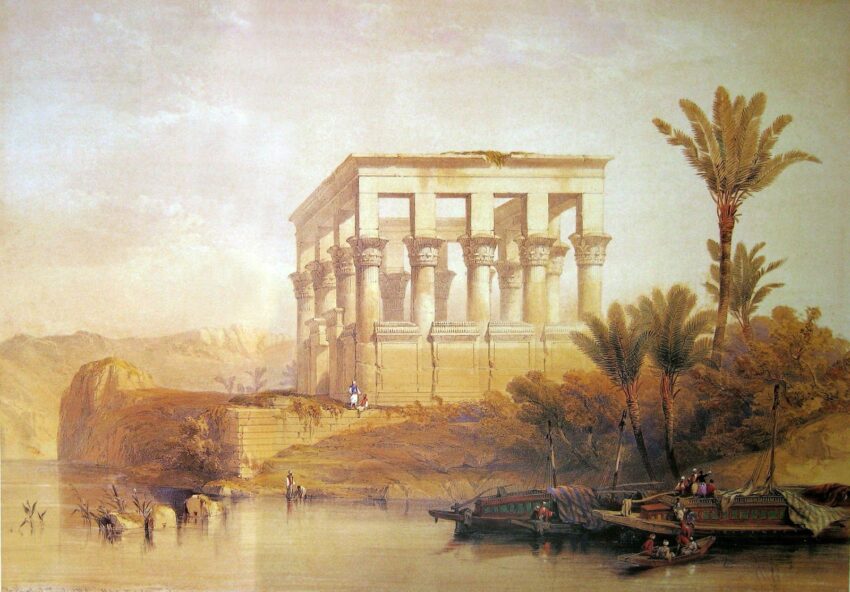

Ancient Egypt was a favoured topic for musings by tourists and armchair travellers alike during the 19th century. Scouring the Nile for remnants of a great and distant past, the temples and tombs of a forlorn civilisation half buried in the sand spoke to the romantic minds of many. Mary Elizabeth Coleridge, although she herself never visited the land, comments on the downfall of Egypt:

Egypt’s might is tumbled down

Down a-down the deeps of thought;

Greece is fallen and Troy town,

Glorious Rome hath lost her crown,

Venice’ pride is nought.

But the dreams their children dreamed

Fleeting, unsubstantial, vain,

Shadowy as the shadows seemed,

Airy nothing, as they deemed,

These remain.

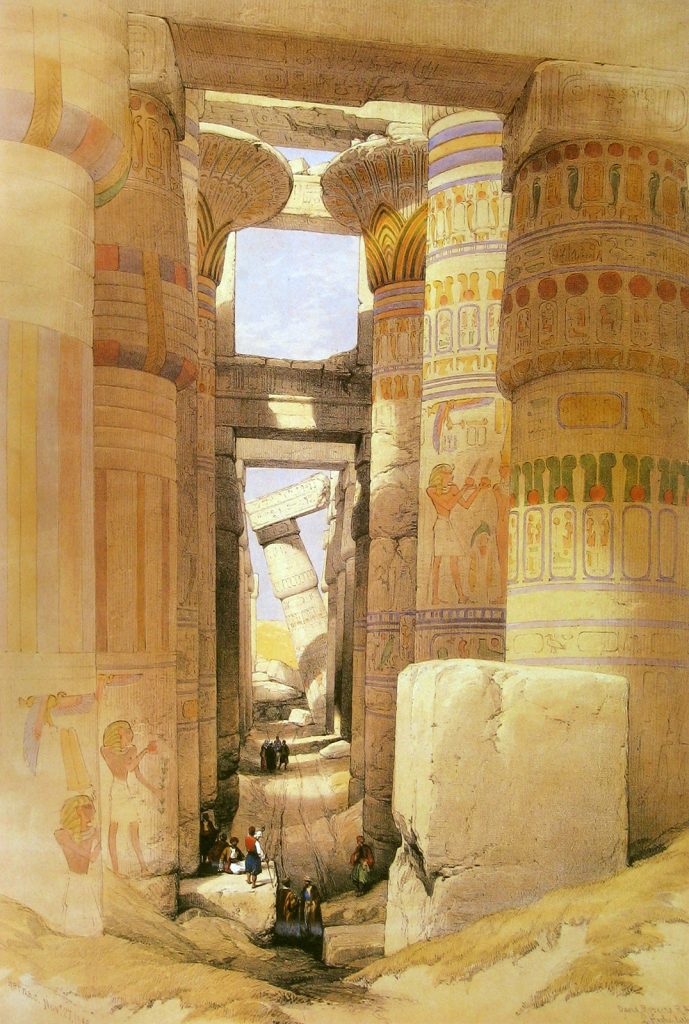

Others were stricken by the splendour of the ancient monuments, such as Mathilde Blind, who travelled widely and devoted a volume of poems to the Orient:

Ancient of Days! Before the Trojan Wars

You towered as now in your colossal prime,

Watching the rosy footed morning climb

O’er far Arabia’s flushing mountain bars.

Despite your weird disfigurement and scars

You dwarf all other monuments. Sublime

Survivors of old Thebes! you baffle Time,

And sit in silent conclave with the Stars.

Ah, once below you through the glittering plain

Stretched avenues of Sphinxes to the Nile;

And, flanked with towers, each consecrated fane

Enshrined its god. The broken gods lie prone

In roofless halls, their hallowed terrors gone,

Helpless beneath Heaven’s penetrating smile.

But best of all perhaps is this children’s poem, written by American author Mary Mapes Dodge, which aptly describes the conduct of both cats and children:

Long, long ago, in Egypt land,

Where the lazy lotus grew,

And the pyramids, though vast and grand,

Were rather fresh and new,

There dwelt an honored family,

Called Scarabéus Phlat,

Whose duty ’t was all faithfully

To tend the Sacred Cat.

They brought the water of the Nile

To bathe its honored feet;

They gave it oil and chamomile

Whene’er it deigned to eat,

With gold and precious emeralds

Its temple sparkled o’er,

And golden mats lay thick upon

The consecrated floor.

And Scrabéus Phlat himself—

A man of cheerful mood—

Held not his trust from love of pelf,

For he was very good.

He thought the Cat a catamount

In strength and majesty;

And ever on his bronzèd face

He wore a look of glee.

And Mrs. Scarabéus Phlat

Was smiling, bright, and good;

For she, too, loved The Sacred Cat,

As it was meant she should.

Never a grumpy syllable

Came from this joyous pair;

And all the neighbors envied them

Their very jolly air.

When Scarabéus went to find

the Sacred Cat its store,

The pretty wife he left behind

Stood smiling at the door.

He knew that quite as smilingly

She’d welcome his return,

And brightly on the altar stone

The tended flame would burn.

The Sacred Cat was different quite;

No jollity he knew;

But, spoiled and petted day and night

Only the crosser grew.

Yet still they served him faithfully,

And thought his snarling sweet;

And still they fed him lusciously,

And bathed his sacred feet.

So far, so good. But hear the rest:

This couple had a child,

A little boy, not of the best,—

Rameses, he was styled.

This little boy was beautiful,

But soon he grew to be

So like The Cat in manners,—oh!

’T was wonderful to see!

He might have copied Papa Phlat,

Or Mamma Phlat, as well;

And why he didn’t think of that

No mortal soul could tell.

It wasn’t want of discipline,

Nor lack of good advice,

But just because he didn’t care

To be the least bit nice.

Besides he noticed day by day

How ill The Cat behaved,

And how (whatever they might say)

His parents were enslaved;

And how they worshipped silently

The naughty Sacred Cat.

Said he, “They’ll do the same by me,

If I but act like that.”

At first the parents said: “How blest

Are we, to find The Cat

Glow, humanized, within the breast

Of a Scarabéus Phlat!”

But soon the neighbors, pitying,

Whispered: “’T is very sad!

There’s no mistake,—that little one

Of Phlat’s is very bad!”

He snarled, he squalled from night till morn,

And scratched his mother’s eyes,

The Sacred Cat, himself, looked on

In envious surprise.

And here the record suddenly

Breaks off. No more we know,

Excepting this: That happy pair

Soon wore a look of woe.

Yes, then, and ever afterward,

A look of pain they wore.

No more the wife stood smilingly

A-waiting at the door.

No more did Scrabéus Phlat

Display a jolly face;

But on his brow such sadness sat

It gloomied all the place.

So, children, take the lesson in,

And due attention give:

No matter when, or where, or how,

Mothers and fathers live,

No matter be they Brown or Jones,

Or Scarabéus Phlat,

It grieves their hearts to see their child

Act like a naughty cat.

And Sacred Cats are well enough

To those who hold them so;

But—oh, take warning of the boy

In Egypt long ago!

For those interested, AUC Press has published a pretty little anthology of 19th century verse featuring ancient Egypt.

Brilliant all.

Thank you for this beautiful and informative illustrative essay and poems. The images are lovely and the poems are incredible.