Yesterday was International Women’s Day. It strikes me as odd that half the world’s population gets only one specific day per year to demonstrate for equal rights. I suggest that for the next couple of thousand years, every single day is devoted to women’s rights. Then we might call it even.

To focus on the positive, there were many remarkable women who pioneered in travelling, exploring and excavating in Egypt. As an Egyptologist, I am thrilled to walk in their footsteps. I’d like to honour some of these women here. In the future, I might dedicate blog posts to each individually, or perhaps even write a book about them.

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), before serving as a nurse in the Crimean War, travelled up the Nile on a dahabiyeh in 1849-50. An account of her journey is preserved in her Letters from Egypt, which have only recently been published. Nightingale, sailing all the way to Abu Simbel, was overcome with emotion on seeing the beauty and splendour of the remote temples of Ramses II, and revelled for a couple of days in a new-found freedom:

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), before serving as a nurse in the Crimean War, travelled up the Nile on a dahabiyeh in 1849-50. An account of her journey is preserved in her Letters from Egypt, which have only recently been published. Nightingale, sailing all the way to Abu Simbel, was overcome with emotion on seeing the beauty and splendour of the remote temples of Ramses II, and revelled for a couple of days in a new-found freedom:

“You look abroad and see no tokens of habitation; the power of leaving the boat and running up to the temple at any hour of the day or night, without a whole escort at your heals; the silence and stillness and freedom of it were what we shall never have again.”

– Florence Nightingale

Further reading:

Florence Nightingale – Letters from Egypt

Anthony Sattin – A Winter on the Nile

Lady Lucie Duff Gordon (1821-1869) left the damp streets of London to spend the last years of her life in Egypt in an attempt to contain her tuberculosis. For seven years she lived in a house in the Luxor temple, surrounding herself with a circle of important locals and visiting Europeans. During this time, she wrote moving letters to her family at home, which are testimony to her great interest in the language and customs of the people around her, and her love for the ‘Arab way of life’.

Lady Lucie Duff Gordon (1821-1869) left the damp streets of London to spend the last years of her life in Egypt in an attempt to contain her tuberculosis. For seven years she lived in a house in the Luxor temple, surrounding herself with a circle of important locals and visiting Europeans. During this time, she wrote moving letters to her family at home, which are testimony to her great interest in the language and customs of the people around her, and her love for the ‘Arab way of life’.

Read online:

Lucie Duff Gordon – Letters from Egypt

Amelia Edwards (1831-1892) toured Egypt in the winter of 1873-74, travelling the usual route from Cairo to Abu Simbel and back in the rich embrace of a dahabiyeh houseboat. Having returned to England, she wrote a vivid account of her journey, A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1877). She became an advocate for the preservation and research of ancient monuments, co-founding the Egypt Exploration Fund (later Society) in 1882. With the support of this Fund, the archaeologist William Flinders Petrie began his various excavations in Egypt.

Amelia Edwards (1831-1892) toured Egypt in the winter of 1873-74, travelling the usual route from Cairo to Abu Simbel and back in the rich embrace of a dahabiyeh houseboat. Having returned to England, she wrote a vivid account of her journey, A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1877). She became an advocate for the preservation and research of ancient monuments, co-founding the Egypt Exploration Fund (later Society) in 1882. With the support of this Fund, the archaeologist William Flinders Petrie began his various excavations in Egypt.

Read online:

Amelia Edwards – A Thousand Miles up the Nile

Alexandrine Tinne (1835-1869) was the daughter of a wealthy Dutch merchant, who took her mother and aunt along on several dangerous expeditions to the interior of the Sudan. Not writing down a single word herself (besides trivial communications to her family at home), we must extract her story from the journals of her travel companions, who both perished on the journey. She herself was ultimately killed in a violent attack by Tuaregs in the Sahara desert.

Alexandrine Tinne (1835-1869) was the daughter of a wealthy Dutch merchant, who took her mother and aunt along on several dangerous expeditions to the interior of the Sudan. Not writing down a single word herself (besides trivial communications to her family at home), we must extract her story from the journals of her travel companions, who both perished on the journey. She herself was ultimately killed in a violent attack by Tuaregs in the Sahara desert.

Further reading:

Robert Joost Willink – The Fateful Journey

Margaret Murray (1863-1963) was a pioneer Egyptologist, feminist and archaeology lecturer. She worked as assistant of Petrie at Abydos in 1902-03, and copied tomb reliefs at Saqqara in 1903-04. Being one of the first Egyptology teachers at UCL, she published at an unprecedented rate and taught a generation of Egyptologists. Above all she was witty, as the title of her autobiography (My First Hundred Years, 1963) demonstrates.

Read online:

Article about Margaret Murray by Ruth Whitehouse in Archaeology International

Margaret Murray (third figure) unwrapping a mummy

Margaret Murray (third figure) unwrapping a mummy

Hilda Urlin (1871-1957) was hired by Flinders Petrie as an artist, but the two married and worked together for the rest of their lives. Accompanying Petrie on his every dig (except when they had young children), she assisted in copying scenes and inscriptions, drawing ceramics, recording finds, writing excavation reports, surveying, dating prehistoric material, and eventually excavating on her own. Every girl’s dream!

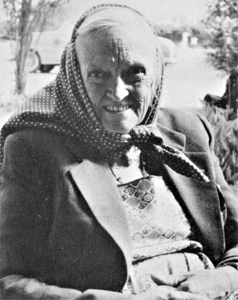

Hilda Urlin at Abydos

Hilda Urlin at Abydos

Winifred Blackman (1872-1950) was a schooled anthropologist who researched the customs and beliefs of the ordinary Egyptian population, resulting in her book The Fellahin of Upper Egypt (1927). Living among the villagers and listening to their stories, she slowly won their trust and was able to paint a detailed picture of life along the Nile Valley.

Myrtle Florence Broome (1887-1978) spent eight seasons copying painted scenes in the temple of Seti I at Abydos. Having studied under Petrie and Margaret Murray, she joined artist Amice Calverley in 1929 at Abydos, living in a mudbrick house near the temple. Like Omm Sety three decades later, the two ladies were frequently called upon by local villagers for medical help. Beside their epigraphic work, which lasted until 1938 when it was interrupted by the Second World War, they travelled widely in the area.

Read online:

Biography of Myrtle Florence Broome

Gertrude Caton-Thompson (1888-1985) gained her interest in archaeology on a trip to Egypt with her mother in 1911. At UCL she studied under Margaret Murray, Flinders Petrie and Dorothea Bate. In the 1920’s she worked as an archaeologist at Abydos, Badari and Qau el-Kebir. She was especially interested in prehistoric Egypt. While working at Badari, she meticulously excavated and recorded the prehistoric settlement of Hemamieh. With geologist Elinor Wight Gardner she began surveying the Fayum in 1925, and worked at Kharga Oasis in 1930. She set a new standard for detailed excavation work.

Gertrude Caton-Thompson (1888-1985) gained her interest in archaeology on a trip to Egypt with her mother in 1911. At UCL she studied under Margaret Murray, Flinders Petrie and Dorothea Bate. In the 1920’s she worked as an archaeologist at Abydos, Badari and Qau el-Kebir. She was especially interested in prehistoric Egypt. While working at Badari, she meticulously excavated and recorded the prehistoric settlement of Hemamieh. With geologist Elinor Wight Gardner she began surveying the Fayum in 1925, and worked at Kharga Oasis in 1930. She set a new standard for detailed excavation work.

Mary Chubb (1903-2003) joined the EES as a secretary to pay for a sculpture course, and ended up participating in the 1930’s dig at Tell el-Amarna. There she discovered two heads of Amarna princesses, as she describes in her book Nefertiti Lived Here (1954). Being the first professional excavation administrator, she was a key part of the excavation team, setting new standards of accuracy for archaeological publications.

Further reading:

Mary Chubb – Nefertiti Lived Here

Dorothy Eady or Omm Sety (1904-1981) was a remarkable woman who, after falling down a flight of stairs at the age of three, began believing that she had been the lover of Seti I in her former life. Her longing for Egypt brought her first to the British Museum, where she was taught hieroglyphs by E.A. Wallis Budge, then on to Cairo, where she worked with Selim Hassan and Ahmed Fakhry while living near the Giza pyramids, and finally to Abydos, where she recognized the temple of Seti I as her home and spent the rest of her life as its Keeper. Her lovely story is recounted by Jonathan Cott (The Search for Omm Sety, 1987). In spite of her eccentricity, Omm Sety has always been regarded highly for her knowledge and character by the archaeologists and Egyptologists she met and worked with.

Dorothy Eady or Omm Sety (1904-1981) was a remarkable woman who, after falling down a flight of stairs at the age of three, began believing that she had been the lover of Seti I in her former life. Her longing for Egypt brought her first to the British Museum, where she was taught hieroglyphs by E.A. Wallis Budge, then on to Cairo, where she worked with Selim Hassan and Ahmed Fakhry while living near the Giza pyramids, and finally to Abydos, where she recognized the temple of Seti I as her home and spent the rest of her life as its Keeper. Her lovely story is recounted by Jonathan Cott (The Search for Omm Sety, 1987). In spite of her eccentricity, Omm Sety has always been regarded highly for her knowledge and character by the archaeologists and Egyptologists she met and worked with.

Further reading:

Jonathan Cott – The Search for Omm Sety

Herta Theresa Mohr (1914-1945) was an Austr ian Egyptologist in Leiden, who published a pioneering iconographical study on the tomb chapel of Hetepherakhet (my thesis subject), under the most dire of circumstances. Being a woman in a predominantly male academic society, and a Jewess at the brink of the Second World War, her unfinished work is both a sad and inspiring testimony. She died somwhere between Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, aged around 30.

ian Egyptologist in Leiden, who published a pioneering iconographical study on the tomb chapel of Hetepherakhet (my thesis subject), under the most dire of circumstances. Being a woman in a predominantly male academic society, and a Jewess at the brink of the Second World War, her unfinished work is both a sad and inspiring testimony. She died somwhere between Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, aged around 30.