Sometimes in life, things happen at the right moment. When Koen Donker van Heel encouraged me to start my own business, I hadn’t read his new book Mrs. Tsenhor yet, which was published in 2014 by the always lovely AUC Press (hardcover, nice design, sparkling white pages). Now that I have, I am affirmed in my beliefs that (1) you should never give up, (2) you should do what you love and (3) you should be economically clever about it. For a book about Demotic contracts that is not primarily written for an Egyptological audience, this is foremost a delightful read.

Sometimes in life, things happen at the right moment. When Koen Donker van Heel encouraged me to start my own business, I hadn’t read his new book Mrs. Tsenhor yet, which was published in 2014 by the always lovely AUC Press (hardcover, nice design, sparkling white pages). Now that I have, I am affirmed in my beliefs that (1) you should never give up, (2) you should do what you love and (3) you should be economically clever about it. For a book about Demotic contracts that is not primarily written for an Egyptological audience, this is foremost a delightful read.

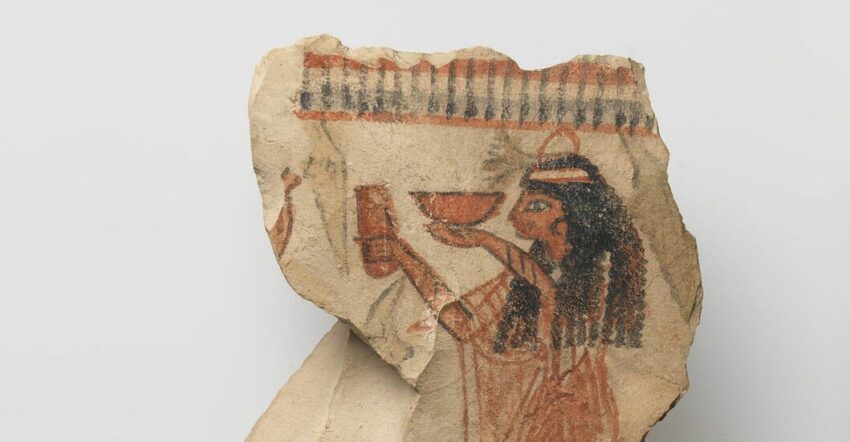

Mrs. Tsenhor lived during the 6th century BCE, on the brink between the 26th Saite dynasty and the 27th Persian one. For 60 years, she lived and worked in Thebes as a choachyte, providing the offerings for a number of wealthy (and dead) clients. Every working day, she would set out with her water-carrying donkey and/or slave boy to visit several tombs in the Assasif and perform her duties. From her papyri now scattered in museums throughout Europe, an image of a businesswoman appears, who managed and acquired her own property and cleverly arranged the division of her inheritance during life. Her daughter from her second marriage would thus gain an equal share compared to her son from her first marriage, making Tsenhor somewhat of an early feminist.

Court proceedings such as this were minutely recorded in the Demotic and even rarer Abnormal Hieratic script. The latter is aptly described by Donker van Heel as bordering on cryptography: ‘something that might have been designed in a dream by Salvador Dalí on LSD, 2,500 years ago’ (p. 34). Wait, what?

Whereas Egyptological literature can be awfully dry and stand-offish, and popular Egyptological literature has a tendency to sound patronizing, Donker van Heel’s prose is refreshing. In a complex treatise on documents, contracts and legal formulas, the author’s witty and (self) mocking tone can be a relief. (‘Until 1999, probably no one in Egyptology devoted too much attention to the practical problems of women having their period in Egypt’). He treats the topics personally, revealing his passion as an Egyptologist and as a human being (demonstrating that Egyptologists, after all, are human beings too). Detailed information is interspersed with historical fact (Amasis was a party animal) and many examples ranging from the Old Kingdom to the Coptic Period. That other great source of documentary information, New Kingdom Deir el-Medina, is of course not overlooked. The story is related in a compact, entertaining manner that provokes a potential enthusiasm for classes in Abnormal Hieratic(!).

There are gems of truth to be found in the book, formulated in occassional one-liners:

- In Egyptology, one quickly becomes used to accepted interpretations changing back and forth for a hundred years or so without direct result (p. 178).

- The question is whether any of them [Coptic women] would have paid heed to admonitions by – as so often – a man in a skirt. (…) Maybe [the monk] Pisentius – like so many religious men – simply had a problem with women as a source of lust and temptation (p. 71-72).

- We sense the age-old family problem still encountered today: it is always the same brothers and sisters caring for their parents, while the others prefer to look the other way or are too busy leading their own lives (p. 187).

- This is a golden rule in hieratic and demotic papyrology: if your solution makes things more complicated, it is probably not the best solution (p. 86).

- It is often overlooked, but the ancient Egyptians were a very practical people in their religious beliefs (p. 167).

Donker van Heel poses interesting questions (did choachytes keep mummies stashed around? What’s with all these menstruating women under the stairs?), and brings to life ancient individuals with their quirky character traits intact. The book is not for the feeble, but highly enjoyable for those with a little Egyptological (or even classical?) knowledge.

One final truth derived from the book is that ‘sometimes writing books – just like life itself – hinges on people telling you to shut up and get to work’ (p. xv). Like Mrs. Tsenhor (and thanks to the author’s encouragement), I am now my own boss. One week after starting my own business, I was furthermore offered a job at Leiden University. This allows me to combine a steady income with interesting projects and ultimately the chance to pursue a PhD. Somehow it feels like I owe this a little bit to a 2,500 year old Egyptian lady who was clearly wearing the pants.

1 thought on “Mrs. Tsenhor”