The offering chapel of Hetepherakhet, now housed in the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, was once part of a mastaba tomb in the Old Kingdom necropolis at Saqqara. The chapel was excavated hurriedly by the famous archaeologist Auguste Mariette in the 1860’s. At that time, Mariette fanned around Egypt like an archaeological sandstorm, undertaking countless excavations. He summarily described the decoration of the chapel in his main work Les Mastabas de l’Ancient Empire, focusing mostly on the tomb chapel’s inscriptions. The plates he was wont to add were probably lost during the spring tide that ravaged the Egyptian Museum when it was still located at Bulaq. The important work of Mariette only appeared in hand-written French. The precise location of the mastaba of Hetepherachet was not recorded on the accompanying map.

Subsequently, the tomb chapel presumably lay open and bare in the desert sand for a couple of years. Until Gaston Maspero, Mariette’s successor as director of the Antiquities Service, decided for some interesting measures. In the annual report by the Egypt Exploration Fund of 1902-1903, a remarkable message was published, in which Maspero announced the plan for ‘the sale of entire mastabas from Sakkareh to the museums of Europe and America’. It was hoped that by selling complete mastaba chapels (for only the decorated chapels were meant, not the entire mudbrick structures), the museum directors would keep their hands clean of dubiously acquired loose blocks and fragments.

In fact the first of these tomb chapels to be excavated in 1902 was that of Hetepherakhet. It was sold for 200 Egyptian pounds (or 5200 French francs), literally only the cost of its exterment, to Adriaan Goedkoop, a wealthy contractor from The Hague who had an interest in archaeology. He paid the sum and donated the chapel to the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. 70 crates, their value taxed at fl. 3,360 (equivalent to over € 41,000 today) arrived in Leiden in the fall of 1902. During the train transport, one of the crates fell off a wagon, but its contents seemed unharmed. In June 1904, the opening of three new Egyptian halls was celebrated, including the ‘garden hall’ with the already famous mastaba chapel.

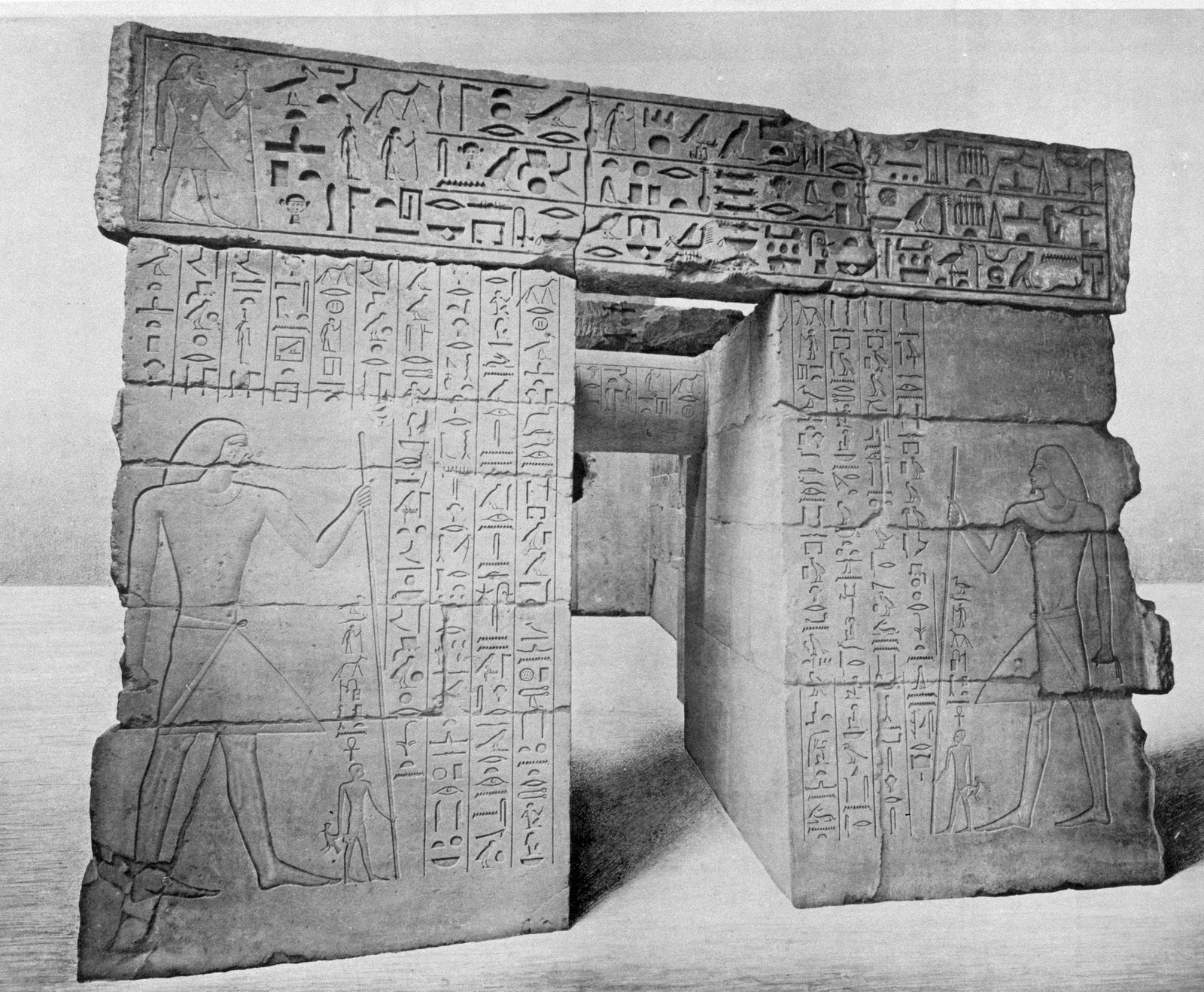

In 1905 the Beschrijving (Description) of the Egyptian collection was published by curator Pieter Boeser. It includes beautiful black-and-white photos of the tomb chapel. Until recently, this was the best photographic record of the monument available. At the end of the 1930’s, a Jewish Egyptologist called Herta Theresa Mohr, who had fled Vienna for Leiden, made a study of the chapel. She created a number of new black-and-white photos, especially of details of the relief scenes. She meant to base her drawings on these photos, but at that moment the war intervened. In 1939, the chapel moved to the cellar of the museum in order to protect it against bombarding. Mohr based her drawings on the older photos by Boeser, that were not large enough to see much detail. Shortly after writing the final introduction to her work, she had to go into hiding and was eventually arrested. Her manuscript, in German, was translated and published by two other Egyptologists and an editor. Shortly before the end of the war, Mohr tragically died in camp Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945. Her story deserves to be told, and I will dedicate an article about her as soon as enough pieces of the puzzle are in place.

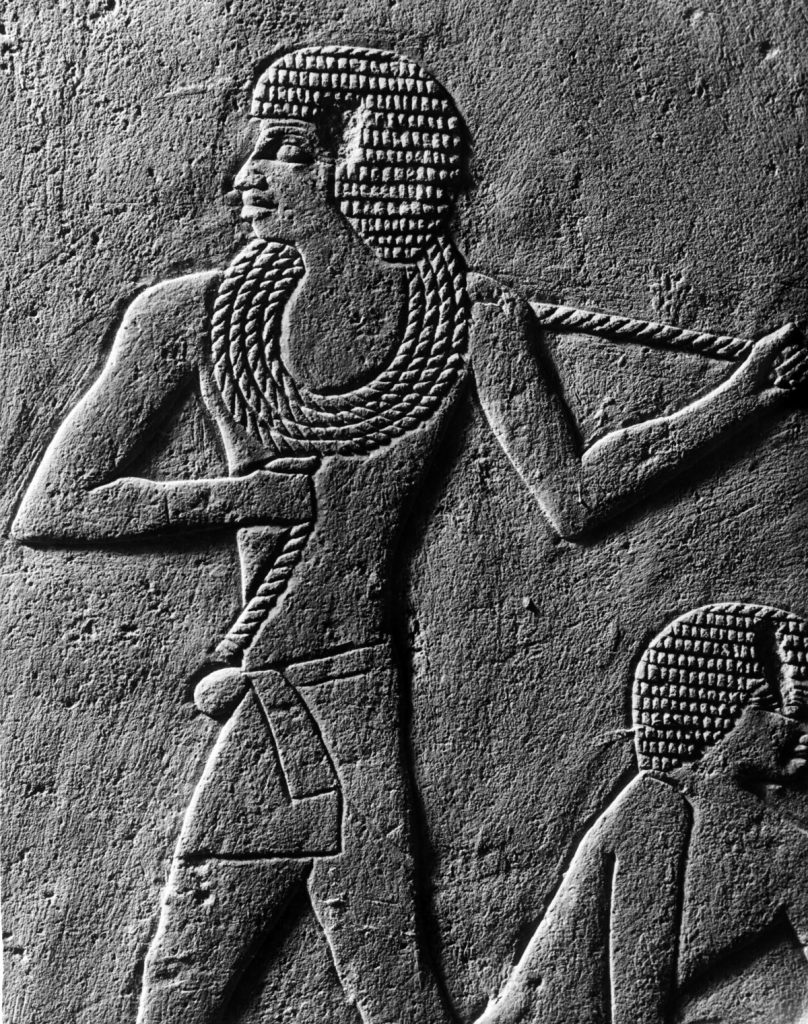

Detail photo made by or for Herta Mohr (from the RMO archives)

The tomb and its owner

Hetepherakhet was a high official during the 5th Dynasty of Egyptian history (around 2400 BCE). He was a judge and priest of Ma’at (the goddess of justice and social order), but also performed duties at the pyramids complex of king Neferirkare and the sun temple of king Niuserre. These were both located at Abusir, just north of Saqqara. The small (5.5 m2) but finely executed chapel was originally placed in the east side of the mastaba complex, which was over 300 m2 in total.

The facade, showing Hetepherakhet in his official attire on both sides of the entrance, gives way to a small corridor leading to a rectangular chamber. One immediately runs up against the false door in the west wall, while the serdab (a closed-off room with a peephole in which wooden or stone statues of the tomb owner were set up) was to be found behind the south wall. The burial shaft, that ran from the roof of the mastaba into the bedrock, was not connected to the offering chapel. A round offering table with the name and titles of Hetepherakhet oddly enough was found inside the mastaba of Ka’aper, in a completely different part of the Saqqara necropolis.

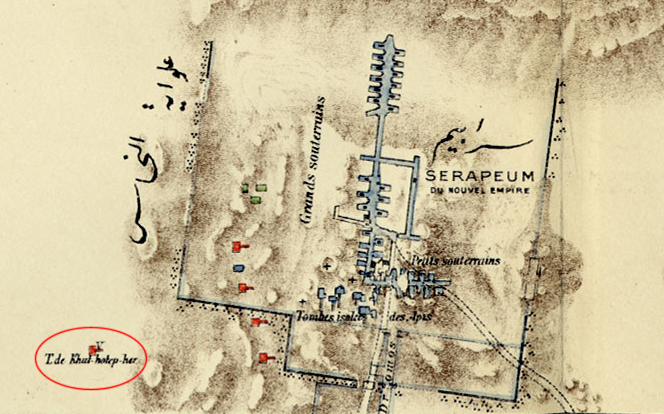

Judging by later maps (chiefly by Jean-Jacques de Morgan in 1897), the mastaba of Hetepherakhet must have been located west of the pyramid complex of Djoser, on the edge of the necropolis and near the later Serapeum.

Location of the mastaba of Hetepherakhet on the map of Jean-Jacques de Morgan (1897)

The offering chapel (the accessible part of the mastaba where relatives and visitors could perform the offering cult), contains scenes in shallow raised relief of excellent quality. Many basic themes of the so-called ‘scenes of daily life’ are present: offerings and offering bearers, the funeral procession, inspecting of agricultural activities by the tomb owner, the funerary banquet, spearfishing in the marshes, and other water-related themes, such as catching water fowl with a hexagonal clap-net, the crossing of water by cattle, and the catching and cleaning of fish. Also, less common scenes are depicted, such as the catching of songbirds and herding of goats.

Through this decoration program, the status of the tomb owner was expressed, as well as the preparations for his funeral depicted. No afterlife is shown with the judgement of the gods, as was common in later eras, but a timeless present in which Hetepherakhet neatly performed his social role. The crux was that his name and image should not be lost and the stream of physical and spoken offerings would not dry out. The fact that his chapel is still being visited on an almost daily basis, that we know his name and that Egyptologists can even read out the offering formulas, shows that Hetepherakhet has succeeded in his design.

Bread and beer

The basis of these important offerings was made up of bread and beer. This staple food was consumed by members of all layers of Egyptian society. Wages were primarily paid or at least expressed in units of bread and beer. Experimental archaeology focusing on the type of bread that was used to feed the pyramid builders shows that this was a heavy sourdough bread on which a family could feed for a day. The beer was lightly yeasted, nutritious bread-beer. Emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) are both archaeologically attested, and seem to have been the basis for both bread and beer. It is however difficult to correlate the Egyptian terms it and bedet with specific types of grain.

The baking of bread and brewing of beer is almost always shown side by side in Old Kingdom tomb scenes. In about 40 published tombs from the area surrounding the capital Memphis you will find this theme, as well as in about 20 provincial tombs. At least 10% of all known and published Old Kingdom elite tombs contained scenes of baking and brewing. This shows that it certainly wasn’t an indispensable theme (only the tomb owner receiving offerings can be considered as such), but important enough to be repeatedly included. Usually the bread-and-beer scene is not present in a focal place in the tomb, but for example in the doorway from one room to the next (e.g. in the tombs of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, Khentika, and Mehu). In the chapel of Hetepherakhet, the scene is shown on the side wall of the corridor leading to the only chamber. In the tomb of Ti, the scene covers and entire wall of what can be considered as the storeroom.

Usually, different phases of the baking process are depicted:

- extracting grain from the granary

- pounding grain with a pestle in a mortar

- grinding and sieving flour

- heating up earthen bread moulds

- pouring in liquid dough

- taking out the finished bread

Consequently, a certain type of dough seems to be processed into beer, by cutting up and soaking it in a vat, or by treading the batter, after which the beer is brewed in a mixing vat, then poured into conical vases and closed off with a lid. Unfortunately, we cannot read the tomb scenes in a specific order like pictures in a comic book. They should be regarded more as a summing up of activities taking place simultaneously within the same space. It is a two-dimensional depiction of a spatial occupation, and it is therefore useful to compare these scenes with wooden models from the Middle Kingdom.

Wooden model from a 12th Dynasty tomb (Berlin Museum, inv. no. 1366). Three women are grinding flour (right), heating bread moulds (left) and brewing beer (middle). In the back, a granary is visible (image source: Wikipedia)

Baking and brewing in the tomb of Hetepherakhet

When looking at the bread-and-beer scene in the tomb chapel of Hetepherakhet, the order of the activities is not always clear. Fortunately, there are hieroglyphic captions that often clarify the scenes, but also tend to confuse them. It seems that different types of bread are being produced side by side, plus a half-product that is further processed into beer. The types of bread can further be interpreted by looking at archaeologically attested bread moulds.

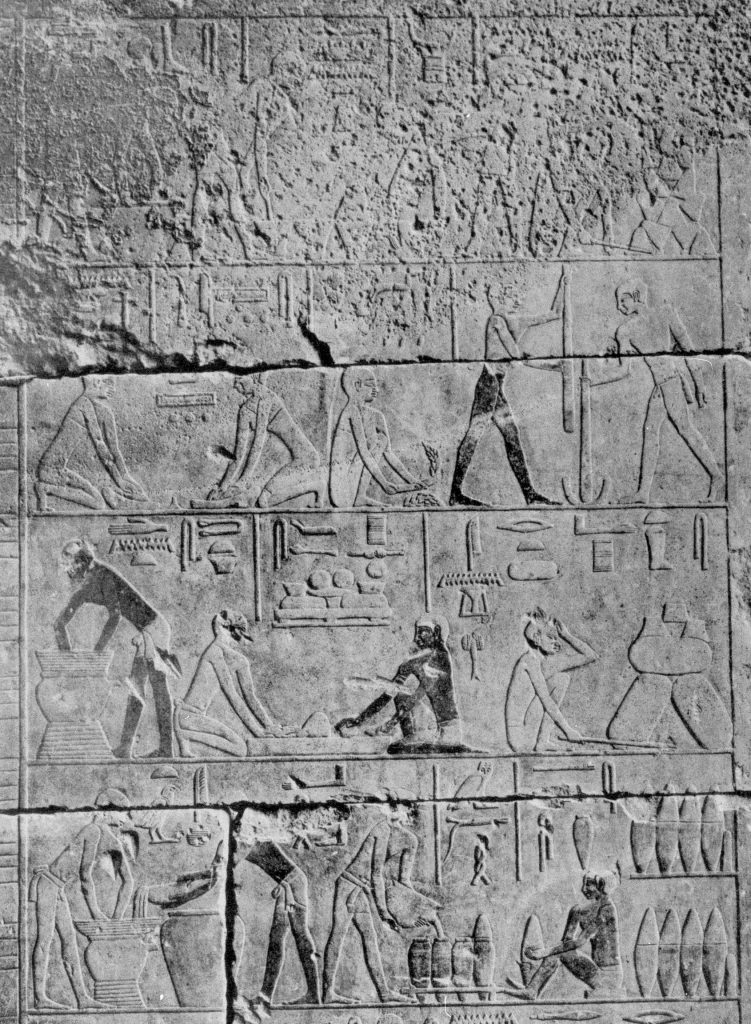

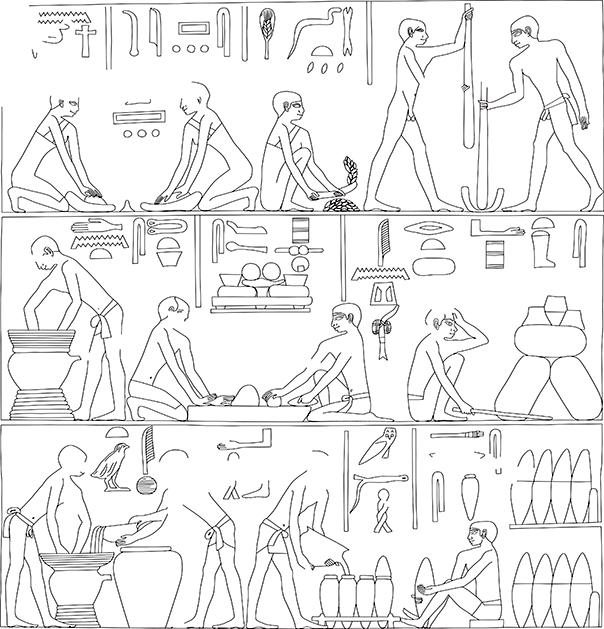

In the upper register, on the far left, a woman is busy with both arms in a large vat of bread dough (shedjet). On the far right, a woman is squatting next to a pile of bread moulds that she is heating. With a stick she pokes in the (presumably) hot ash. From parallels we know that these clock-shaped moulds are called bedja. On her left, a woman bends over a bread mould she has just opened. Left again, a woman checks the quality or degree of cooking of the bread (dough), by sticking a spoon(?) inside it.

The bread-and-beer scene in the tomb of Hetepherakhet

In the second register, people are processing grain. On the right, two men are pounding grain with a pestle in a mortar. In the middle, a woman is sieving bedet (usually translated as emmer wheat), by throwing it in the air and catching the heavier particles. The woman on the far left is grinding (nedj), while her colleague is grinding a specific type of malted barley (besha).

In the third register, the squatting man on the far right is heating up so-called aperet-moulds. These are large, flat, oval dishes, that are here shown in their full width. The man protects his face from the hot glow. On the far left, a man is soaking setjet-dough, which is the same name given to the three moulds on top of the aperet-moulds. In the middle, two men are shaping pezen-bread, which in turn corresponds to the aperet-moulds.

In the fourth and final register of this scene, we clearly see beer production depicted: on the left, a man is brewing beer in a spouted vessel. His colleague meanwhile pours liquid from another vat into the mixing vat. In the middle, a man fills beer jars with brewed beer, while the man on the right seals these so-called des-jars with what appears to be a clay stopper.

The lower three registers of the scene (drawing by author)

All in all, the scene in Hetepherakhet highlights many elements of the baking and brewing process, but the specific order of the stages of production is not directly evident. Different types of bread and dough are processed in their own way. The activities are shown in a certain order, but in reality they took place side by side. By comparing the same theme as it is represented in different tombs, we obtain a reasonable picture of the process.

The bread and beer making scenes also hint at certain male/female ratios. We usually find women grinding and sieving grain, making bedja bread and brewing beer, while men are concerned with the granary and administration. The pounding of grain is usually done by two men (but also sometimes by a single woman), and when overseers are required (e.g. in the tomb of Ti), these are always men. This labour division could be partially directed by the degree of organization, varying from household production to small-scale industries. Bedja bread seems to be the type of bread that was consumed on a daily basis. One scene in the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep is characteristic: a woman is grinding grain while her child is clutching her neck. While her colleague urges her to keep up the tempo, she soothes her son with the words: ‘See, I’m here, my love!’

The bread and beer making scenes also hint at certain male/female ratios. We usually find women grinding and sieving grain, making bedja bread and brewing beer, while men are concerned with the granary and administration. The pounding of grain is usually done by two men (but also sometimes by a single woman), and when overseers are required (e.g. in the tomb of Ti), these are always men. This labour division could be partially directed by the degree of organization, varying from household production to small-scale industries. Bedja bread seems to be the type of bread that was consumed on a daily basis. One scene in the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep is characteristic: a woman is grinding grain while her child is clutching her neck. While her colleague urges her to keep up the tempo, she soothes her son with the words: ‘See, I’m here, my love!’

Sources

- Mariette, A., Les Mastabas de l’Ancien Empire (1889), 340-348.

- Griffith, F.Ll., Egypt Exploration Fund Archaeological Report 1902-1903 (1903), 12.

The full phrase goes: “A scheme has been approved for the sale of entire mastabas from Sakkareh to the museums of Europe and America. It is hoped that when such can be obtained at a moderate figure the directors of museums will be less eager to buy odd blocks and fragments broken out by robbers, and that so the robbers will give up their detestable trade.” - Boeser, P.A.A., De monumenten van het Oude Rijk, Beschrijving van de Egyptische verzameling in het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden te Leiden I (1905), 11-18, pl. V-XXI.

- Mohr, H.Th., The mastaba of Hetep-her-akhti: study on an Egyptian tomb chapel in the Museum of Antiquities Leiden (1943).

- Faltings, D., Die Keramik der Lebensmittelproduktion im Alten Reich (1998).

With thanks to Prof Dr Maarten Raven from the National Museum of Antiquities for providing information about the acquisition of the tomb chapel, as well as access to the museum’s archives, and to Hans van den Berg for the composite photo on which my illustration of the scene is based.

The original article in Dutch can be found here:

Beek, N. van de, Brood en bier voor Hetepherachet, in: 40 jaar Dispuut Pleyte (2015), 54‐63.

A project is currently being undertaken in cooperation with the National Museum of Antiquities to fully document and publish the tomb chapel of Hetepherakhet using modern means. Stay tuned.

2 thoughts on “Bread and beer for Hetepherakhet”