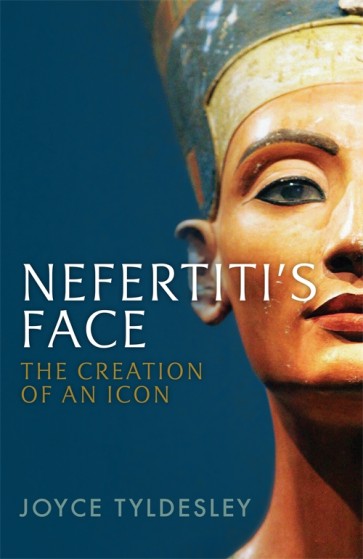

When Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley visited Bolton Museum as a child, she was unaware that the bust of Nefertiti she admired there was in fact a replica. She soon found copies of the work popping up in museums around England. The original bust was first displayed when the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun was causing a sensation in the 1920s. At the time, it seemed to appeal to the public imagination as a surprisingly modern form of art deco.

When Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley visited Bolton Museum as a child, she was unaware that the bust of Nefertiti she admired there was in fact a replica. She soon found copies of the work popping up in museums around England. The original bust was first displayed when the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun was causing a sensation in the 1920s. At the time, it seemed to appeal to the public imagination as a surprisingly modern form of art deco.

In fact, the bust had already been discovered years earlier by Ludwig Borchardt’s team at Amarna, in December 1912. In Nefertiti’s Face: The Creation of an Icon, Joyce Tyldesley discusses the meagre facts about Nefertiti’s life, the artist that created her image and her subsequent journey to the west as an icon of beauty as well as controversy. It is an enjoyable little book (186 pages of text), that leaves the reader wanting to know more (42 pages of notes, bibliography and index).

Tyldesley interestingly describes Thutmose, the creator of these and other models of the Amarna royal family, as an artist-businessman, much like Rembrandt and his workshop during the Dutch Golden Age (pardon the comparison – I currently work at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam). We know so much and yet so little about artists in ancient Egypt. Deir el-Medina is overly represented in the record, while craftsmen from other places and periods are barely known by name. Were artists not allowed to sign their work because of the sacredness of what they depicted?

We have come to identify the famous bust with our image of Nefertiti, although it is in fact exceptional (and anonymous). How do we identify the Amarnas (the Kardashians of the ancient world), if not by their cartouches? Nefertiti is known for her ‘feminized’ form of the blue crown, while Kiya is simply identified by her large earrings.

Busts are very uncommon, because they were not considered ‘complete’ images. We know of Old Kingdom ‘reserve heads’, Tutankhamun’s lotus head, ancestors busts from Deir el-Medina and the Amarna artist’s models (most of which are much less ‘finished’ than the Nefertiti bust). A modern art project intended to give Nefertiti a body sparked outrage from the Egyptian community. The sacredness of the image is still under discussion today.

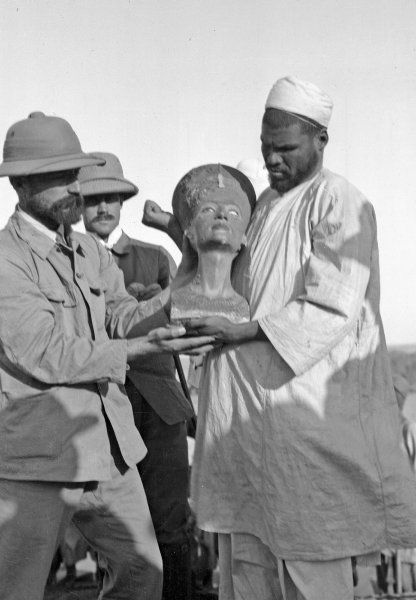

During the Amarna excavations, Borchardt was not always present himself. He relied on Hermann Ranke and experienced local workmen for a large portion of the work. According to the Antiquities Law of 1912, a system of partage was in place that required the findings to be split in half, giving first choice to the Antiquities Service. Two lists were made, one headed by a household shrine, one by Nefertiti. Both collections were inspected and a protocol was signed. A succesful exhibition was then held in Berlin, strangely without the bust.

The discovery of the bust

It was only in April 1924, after the war, that Nefertiti was displayed to the public. Sensing that an error was made, in 1929 negotiations were held for her return to Egypt, but (German) public opinion was against it. Nefertiti had accidentally become part of the national identity of post-war Germany. In 2011, then director of the Supreme Council of Antiquities Zahi Hawass made a formal request to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (officially the keeper of Nefertiti) for return of the bust, which was rejected, and further action was halted by the Arab Spring revolution. The story of Nefertiti seems unfinished, but here the book ends.

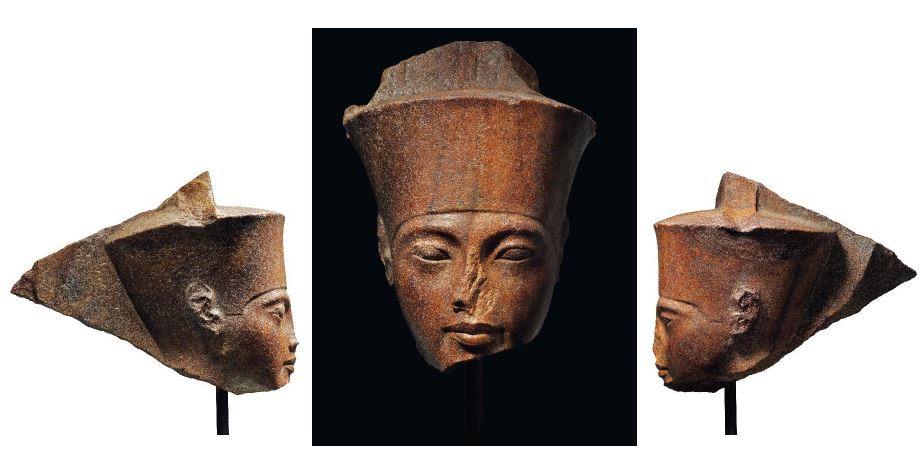

in July this year, an ‘Egyptian head with features of King Tutankhamen’ was offered for sale at Christie’s in London. This statue of brown quartzite representing Tutankhamun as the god Amun seems to originate from the Karnak Temple in Luxor. It was acquired in 1985 from Munich art dealer Heinz Herzer, who was earlier involved in a controversial sale. According to Christie’s, it had been part of the collection of enigmatic Prinz Wilhelm von Thurn und Taxis. Unsurprisingly, the sale of the statue for £4.7 million led to public outcry. Egypt even intends to take legal action.

The Tutankhamun head sold by Christie’s

Although the legality of the sale is dubious at best, there is also the viewpoint of ethics. While ridiculous amounts are being paid for Egyptian antiquities on the art market, an employee (in fact, the director) of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo made just a couple of hundred dollars per month in 2004.

Questions about the legitimacy and ethics of dealing in art and antiquities are now more current than ever. In order for us to continue enjoying this heritage both within Egypt and in collections around the world, the discussion needs to remain open.