When Thomas Cook went bankrupt in September 2019, hundreds of thousands of holiday makers were stranded. Tens of thousands of employees were out of a job, including many local service providers. Thomas Cook and Son was a household name in the travel industry, two men who single-handedly invented organised travel, and paved the way for how many first time travellers to Egypt still experience the Nile today.

When Amelia Edwards visited Egypt in the winter of 1873, the thing to do was to travel by dahabiya, an elegant house boat with sails. After the arrival at Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo, many time went in selecting the right sized dahabiya at the Boulaq quay with the help of a dragoman. The boat would first have to be sunk in order to get rid of rats and other vermin, and would then be fitted with all the amenities required for life on board. This included new curtains, carpets, paintings, a collection of books and of course, a piano. Preparations were carefully described in Murray’s Handbook for Travellers (1847) by John Gardner Wilkinson, himself an avid Nile traveller.

Travelling up the Nile to Aswan could take up to several weeks, depending on the wind and ubiquitous sandbanks, when the boat would have to be towed by the crew. Everything required for the trip had to be taken on board. After more or less rushing south, the return journey would be taken at a more leisurely pace, driven by the Nile stream, with time to visit the many sites. In the preface to the first edition of A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1877), Edwards writes:

“The choice between dahabeeyah and steamer is like the choice between travelling with post-horses and travelling by rail. The one is expensive, leisurely, delightful; the other is cheap, swift, and comparatively comfortless. Those who are content to snatch but a glimpse of the Nile will doubtless prefer the steamer.”

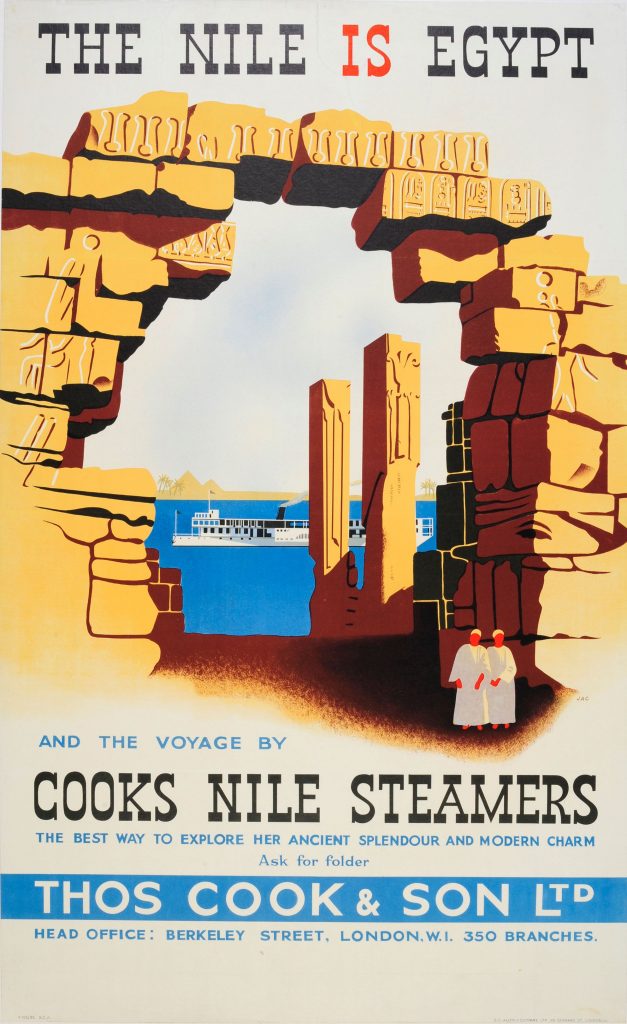

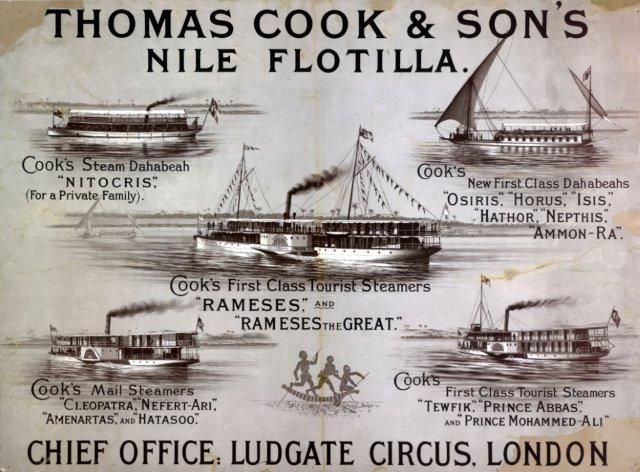

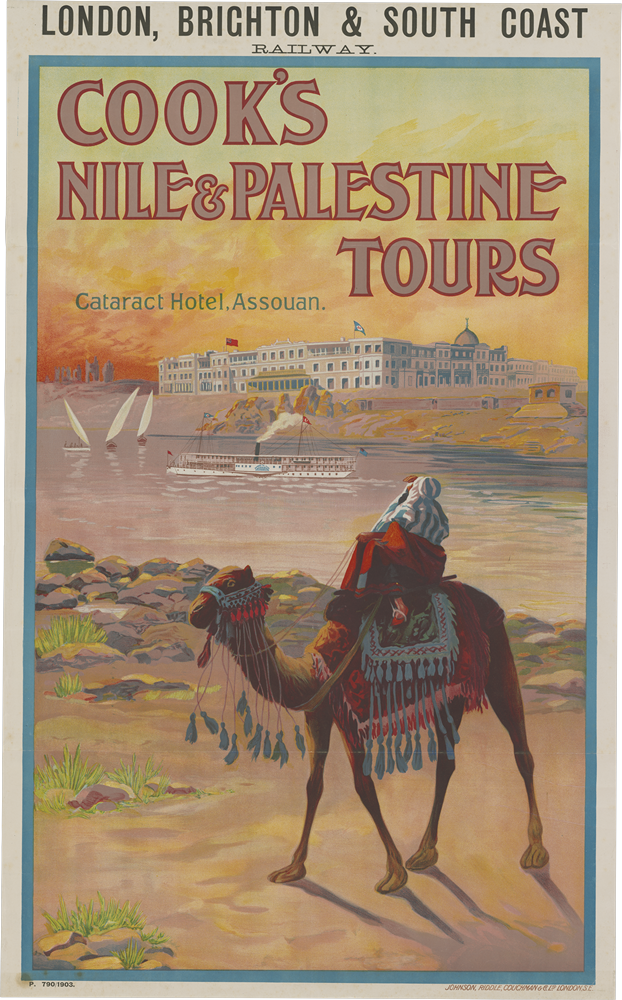

At that time, steamers had begun to appear on the Nile, rivaling the slower and more expensive dahabiyas. While Edwards’ trip cost about £10 per day (“everything included except wine”), tourists would pay but £ 44 (still a considerable sum in today’s terms) for a 20 day cruise to Aswan and back with Cook’s Tours, including food, guides, donkeys and candles to light their way inside dark tombs.

Thomas Cook, born in 1808 in Derbyshire, began his career as a cabinet maker and Baptist missionary, touring the region as an evangelist while distributing pamphlets. The first excursions he organised were walking tours from one town to another in order to attend temperance (anti-liquor) meetings. Next he took people on professional tours to Scotland, the Great Exhibition in London and the Paris World Fair. After numerous trips to Europe and the US, in 1868 he first set foot in the Middle East to test the grounds there.

Cook had opened up shop in London and eventually partnered with his son John, and so in 1871 Thomas Cook & Son was born. John would bring the company commercial success and greatly extended the Nile travel branch. The benefit of travelling with Cook was that negotiated discounts were passed on to the customers, who would pay the travel sum in a single payment. Cook promised security and ease, opening up travel to a wider public and to women who could now join a package tour unchaperoned.

After boarding the Nile steamer at Cairo, a typical itinerary would take the tourist to Memphis and Saqqara around noon, to return to the boat in time for 5 o’clock tea. Bathing would be done aboard in Nile water. For on board entertainment there was a salon with a library and piano. English breakfast was enjoyed on the sun deck, where one could watch the birds, palm groves, fields of sugarcane and river traffic pass by.

On the fourth day, the boat would reach Beni Hassan, with its elaborately decorated Middle Kingdom tombs high up in the cliffs. On day seven the donkeys would be saddled for a visit to the Ptolemaic temple of Dendera. On arrival at Luxor, a moonlit ride would be enjoyed to Karnak. On the West Bank one would visit the impressive temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, the artists’ village of Deir el-Medina and the quiet Ramesseum. The third day in Luxor was devoted to Hatshepsut’s impressive temple at Deir el-Bahari and as a highlight the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. On the way, antiquities could be bought from enterprising consuls, and the occasional crocodile hunt took place.

After the temples at Esna and Edfu, the stone quarries of Gebel el-Silsila and the temple of Kom Ombo, Aswan would be reached on day thirteen. A visit to the islands of Elephantine and Philae was not to be missed. Optionally, the itinerary could be extended with a trip to the second cataract at Wadi Halfa. In one week, the boat would return to Cairo, calling on Luxor, Abydos and Assyut along the way. When the railway line was extended to Luxor in 1898, one could take an even shorter journey from Luxor to Aswan with stops at Edfu, Esna and Kom Ombo, returning to Luxor after a day in Aswan. Essentially, this is the classic nile cruise still enjoyed by countless tourists today.

In the wake of increasing Nile travel, new hotels were opened along the route such as the Old Cataract Hotel in Aswan (built by Thomas Cook in 1899) and the Winter Palace Hotel in Luxor (inaugurated in 1907). The First World War put a temporary stop to touristic activity (although Cook catered to British troops in Cairo), but when the tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered in 1922, tourists again flocked to Luxor. After the Second World War, a new impetus was given to travel in Egypt by the UNESCO rescue campaigns of Philae and Abu Simbel, until at the end of the 20th century 250 cruise boats would crowd the Nile between Luxor and Aswan. Only the 2011 revolution put a damper on this number.

In 2013, I took a cruise on the stretch of the Nile between Luxor and Aswan to commemorate my first trip to Egypt in 2000, which had included a similar voyage. There were fixed times for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and tea with cake was served on deck at 4 o’clock. A jolly psychiatrist in our company was reading Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile, as was my mother, so every time they ran into each other he asked whether she had found a dead body yet. People were lying on deck in swimming attire, reading their e-reader, even though the wind was quite chilly in January. The tour guide, who was meant to keep us all together, kept getting heart attacks when we decided to take a walk rather than a calèche to the temple of Edfu, or wanted to book our own air balloon, with the rest of the group following.

Nile travel will always have its charm, whether it is on a small motor boat to cross the river at Luxor, a felucca for an hour’s trip before dusk, a cruise boat or a dahabiya. Many cruise boats went out of business after the 2011 revolution and the subsequent decrease in tourism, and it was sad to see all the boats lying idle, sometimes sinking along the Luxor banks. Hopefully tourism in Egypt will reinvent itself to find more sustainable ways of travel, so future travellers can continue to enjoy the Nile for a long way to come.

Read more:

-

Edwards, A., A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1887).

-

Humphreys, A., On the Nile in the Golden Age of Travel (2015).

-

Wilkinson, J.G., Hand-book for Travellers in Egypt (1847).

Your document was very interesting as i was researching material on these Thomas Cooks Nile boats, mainly Hathor.

The COLEMAN family who started the Mustard Factory in Norwich has a Wherry named after the Hathor to honour their Son Alan Coleman who died in this boat in Luxor in Feb 1897.

The Wherry has an Egyption enterior and was built in 1905.

Today i am a meet and greet guide on this Wherry hence the interest checking up on background story.

The Wherry is up and running but we need support to maintain it condidtion and thats where i come in.

Thanks for our article.

Barry Elliott

Also found this interesting. Andrew Mellon mentions in “Reflections of a Silver Spoon” using a small version of a Thomas Cook House boat in 1935 on his honeymoon with Mary Conover Mellon.

Natacha Rambova does not mention such a boat but she traveled the Nile in 1934 also on her honey moon while married to the Spanish Count. I imagine this is what they used.

Mary met the Egyptologist Henry James Breasted on her trip and wanted him to write an English translation of the Pyramid Text so she could have it published, but he died a year later.

Natacha met the Egyptologist Howard Carter a year earlier on hers and that would later help her gain access to the Boy Kings Tomb for which he is famous for and while working for Mary’s Bollingen Foundation she would later romp around Egypt for 2 years until one day she walked into the French Museum in Cairo and stole an Egyptologist and then lead the 5 yr expedition that produced six books under Axlendre Piankoff’s name with one again dealing with the Pyramid Text of Unas. It was Mary’s wish to see the Pyramid Text finally translated into English, though she died at the young age of 42 before that happened. However Natacha still made it happen and in some way these Thomas Cook house boats seem to have contributed to that.

When one thinks of meetings on the Nile one might think of Elizabeth Peters character Amelia Peabody who traveled the Nile on a house boat where such meetings could be hours, days and even weeks or months.

Anyways, thank you for preserving this.