The People of the Cobra Province in Egypt

The book starts with an interesting question: were there classes in ancient Egypt? And if so, was there a middle class? Grajetzki points out that we inevitably look to ancient Egypt through the lens of our own current neoliberal, individualistic world view. In the past, ancient Egypt was often explained as either a lost paradise (with equal rights for men and women) or a bad state suppressing its people into building pyramids. The development of Egyptian history from a provider state in the Old Kingdom, restrictive state during the Middle Kingdom and mature state in the New Kingdom (categories by Barry Kemp) likewise supposes an ‘Age of Empires’ kind of evolutionary model based on our own ideas of the ascent of (European) civilization from Greeks/Romans – Middle Ages – Renaissance.

Grajetzki furthermore claims that Egyptologists, often from a middle to upper class background themselves, like to project the ideas they were brought up with on ancient Egyptian culture, including a focus on the scribal elite. This may be a bit blunt as nowadays, many first generation and/or working class students are joining the ranks of Egyptologists, myself being one of them.

Instead of the market economy implied by some Egyptologists, Grajetzki takes a Marxist approach to ancient Egyptian society in which the mode of production was a deciding factor. He defines class as a group of people in society configured by their relative position and relation to production, either aware or unaware. He acknowledges the existence of a ruling class, conscious of their position, set apart by their literacy and boasting autobiographies. A middle class would then consist of farmers and craftsmen who owned property. The lower class or working population would be devoid of property with the possibility of being exploited.

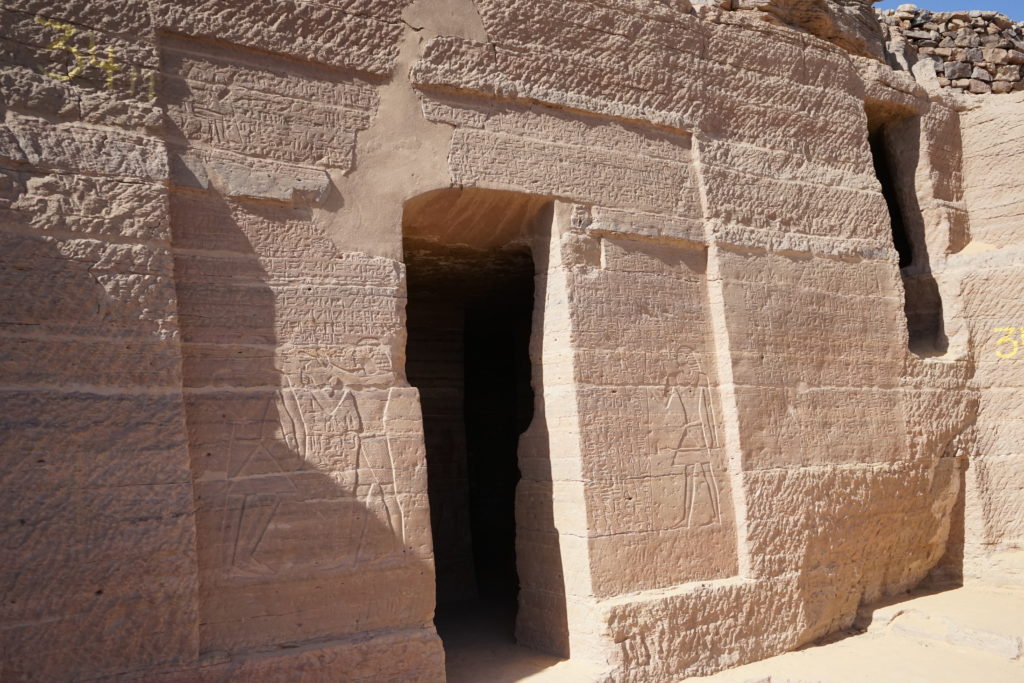

The autobiography of Harkhuf on his tomb in Aswan

For the Old Kingdom, Grajetzki sees a patriarchal system of taxation as well as direct exploitation in the form of corvée labour. There was a strong unity of countryside and town, with towns being purely administrative, religious or commercial units. The population consisted mostly of farmers, although social differences existed. The next step on the Age of Empires ladder would be the feudal Middle Kingdom, with local courts building grand rock-cut tombs such as at Qau. Grajetzki stresses there never developed a land-owning ruling class basing their power on ownership of estates and people (like in our European Middle Ages). Likewise he argues against the term ‘elite’, meaning ‘leading men’ in sociology, although it has been generously used in Egyptological literature in recent decades (e.g. an ‘elite tomb’, often decorated, belonging to a high official).

After these theoretical considerations, Grajetzki discusses the setting of the Wadjet nome. Being the 10th Upper Egyptian province, it encompasses the sites of Qau and Badari. It is attested in a list of provinces from Senusret I’s White Chapel at Karnak as being about 32 km long (3 iteru, 1 kha). On its eastern shore, burials remained well-preserved, while the west bank provided a broad base for agriculture where burials have mostly vanished. Qau was its most important cemetery, although heavily looted and partly destroyed by floods. In the north lies the prehistoric site of Badari. Papyrus Reinhardt describes it as a fertile area, providing 15 sacks of grain per aroura. The province was most likely a conglomeration of small villages, with one central town that could feed up to 600 people. A large part of the population consisted of farmers.

Predynastic Period

In the following five chapters, the book goes on to describe the Wadjet province during different periods, from the Predynastic to the Second Intermediate Period. The earliest substantial human remains were from the Badarian, around 4400 BC. It is hard to get a clear picture of social relations based on the burials from this period, and the impression is gathered of a largely egalitarian society. There is evidence of hunting, herding and agriculture, while people built impermanent dwellings. Female burials are associated with cosmetic palettes, whereas male burials contained more knives. Unfortunately, the original excavator Guy Brunton dug up 5000 tombs in the span of a few years, documenting little information about skeletal remains.

Humans were buried with mats and animal skins to protect the body and pottery vessels, which immediately brings up the question of the ‘symbolic eternal food supply’. Findings of lapis lazuli (from Afghanistan) and obsidian beads (from Yemen or Ethiopia) points to long distance trade or exchange, already for this very early period. Scarce settlement remains included spindle whorls, flint and bone tools, ivory amulets, beads, shells and resin.

Early Dynastic Period

The early dynastic period witnessed the rise of a unified state with a central government ruling from Memphis. It encompasses dynasties 1-3, from 3000-2700 BC. At Wadjet, the dating of early dynastic burials is problematic. 150 graves were originally dated to this period, although many were subsequently reassigned by Kemp to a later date. At Hemamieh, 65 early dynastic burials consisted mostly of simple shaft tombs. Tombs of a local ruling class can be discerned by their high number of important objects (stone vessels, copper items) and the use of brick in the form of staircases and chambers. One tomb may belong either to a priest of Nemty called Hetep, or the priest Nemtyhetep.

No early dynastic settlements were excavated at Qau and Badari, while at Elephantine in the south during the same period we find huts and evidence of metal working and pottery production. During this period, a fully developed administration existed and Wadjet became part of the rest of Egypt. However, writing was still mostly done in the royal residence of Memphis. During the second dynasty, the act of ‘cattle counting’ (collecting of dues) comes in vogue, as well as a new type of pottery: the beer jar. A cemetery of high officials springs up around Memphis, while sacrificial servant burials are found around royal tombs. These were people of a different social status: craftsmen buried with their tools at Saqqara, and women with queenly titles at Abydos.

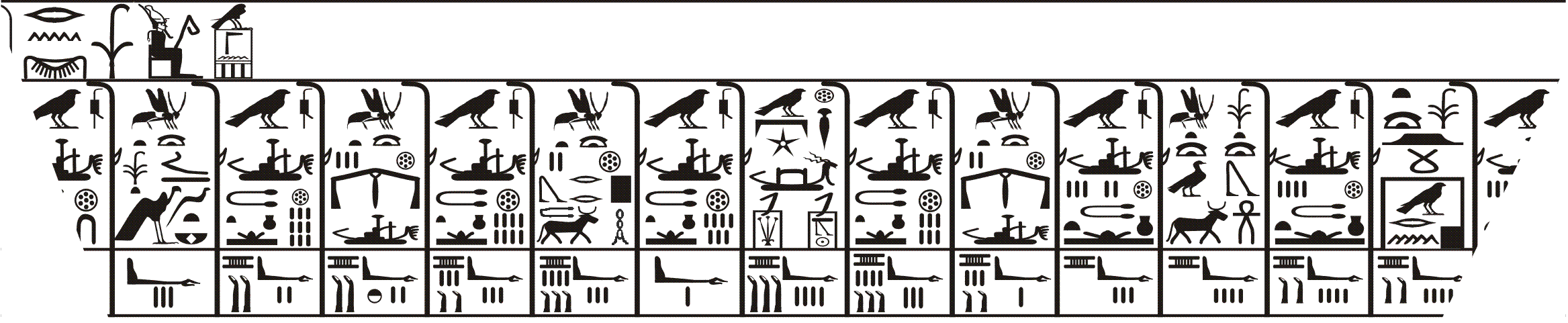

The Palermo Stone lists flood levels and a biannual cattle count under king Nynetjer (source)

The countryside and provinces around Memphis played a role in the food supply, equated by Grajetzki with a tributary mode of production. Free peasants were living in villages, wile resources were annually collected by the ruling class. Local exchange of goods and materials took place.

Old Kingdom

During the 4th-5th dynasties at Wadjet, one finds surface burials and shaft tombs with limited burial equipment. There were pottery and stone vessels, jewelery and tools, staircase tombs belonging to the local ruling class and pot burials for children. Wooden coffins appear in bricked chambers. Certain titles attested in tombs from Giza and Dahshur mention ‘overseers of the work gangs of Upper Egypt’, possibly implying the involvement of Wadjet people in royal pyramid building.

During the later 4th-5th dynasties, tombs of local governors were built at Hemamieh. Tomb A3 belongs to Kakhenet I. In his rock-cut tomb, scenes show the bringing of cattle, a shipyard and dancing women. Grajetzki understands these scenes as an idealistic view of life that was heavily stylized. As an example he mentions the abundance of personal adornments, which were not archaeologically attested. Also the depictions of often fictional domains (although the concept of domains in itself was not fictional), and the ploughing scene. According to Grajetzki, ploughs were not widely used, although the activity is often depicted. He thinks artists from the residence executed a standard program of scenes, and that we know ‘absolutely nothing about how scenes were chosen’. I beg to differ on a number of these points, but I will be able to tell you more once I am well underway with my upcoming PhD thesis on the conceptualization of landscape in Old and Middle Kingdom tombs.

Another point of discussion are the female burials. Decorated tomb chapels at Hemamieh all belong to men. Tombs of men were larger and contained more pottery. However, the Old Kingdom does present us with several examples of households belonging to high society women that were in turn managed by women holding administrative titles. According to Grajetzki, the recent attention to women in ancient Egypt exemplifies how modern world views are projected on the past. Modern women would be in search of role models in history. Popular books present a picture of free Egyptian women with almost the same rights as men. One gets the impression that the author is a bit grumpy about this movement. Personally I highly applaud the recent discussions about gender, race and colonialism in Egyptology and view these as stepping stones to a more diverse view about ancient Egypt. Isn’t Grajetzki’s own attempt at a ‘history from below’ a case in point?

Little is known about the working population at Wadjet, but from Gebelein we have a papyrus containing a list of names and professions giving a rough idea of the structure of a village. There were king’s servants, gang members, hunters, carpenters, scribes, people in charge of goods, documents and the granary, and inspectors to keep everything in check. From what we know at Elephantine and Hierakonpolis, Old Kingdom towns were small but nevertheless equipped with massive walls and a local temple. One would expect the palace of a local governor, pottery kilns and workshops (such at Elephantine and Ayn Asil in the Dakhla Oasis). The central administration provided the palace and royal building projects with resources while the regional administration was in the hands of a local ruling class. New towns were chiefly founded to provide resources for the residence. Until the 6th dynasty, the royal family and high officials were heavily interwoven through marriage. Grajetzki considers local governors and their tombs as outsiders, implanted in the countryside from the central government at Memphis.

End of the Old Kingdom and beyond

A new archaeological phase is clear at Wadjet from 2350 BC. Although the end of the Old Kingdom and the subsequent First Intermediate Period are conventionally seen as a period of decline, the province seems to have thrived with richer burials appearing. Wooden coffins became common and pottery, stone vessels and adornments were provided, as well as clay offering tables and model houses. Women were buried with more jewelery and grindstones, while men stocked up on meat offerings. Figurative amulets and button seals became all the fashion.

In later Middle Kingdom literature (e.g. the Admonitions of Ipuwer) the First Intermediate Period was presented as a period of distress, local warfare and famine. Although the governor’s palace at Balat and the local temple at Mendes were sacked and burned, life at Wadjet went on without much of a break. Several reasons are given for the end of the Old Kingdom, from a weakening of the central government and ineffective bureaucracy to foreign invaders and climate change. Again, this is a topic that has my interest in light of my upcoming PhD thesis.

Middle Kingdom and beyond

Around 1950 BC, a new phase begins at Wadjet. While Senwosret I reorganizes Egypt on a grand scale, monumental tombs are being built at Qau. These tombs for local governors rank among the largest private tombs of the Middle Kingdom. When I visited Qau el-Kebir in 2008, I was thoroughly impressed. Although heavily looted and destroyed, through layers of bat guano and soot, a glimpse of the size and grandeur of these tombs can be felt. Reminiscent of the royal funerary complexes of the Old Kingdom, or Nubian temples as Petrie suggested, these tombs consisted of a gateway, long causeway and cult chapels carved into the rock. A patterned bit of ceiling can be here and there be discerned, but unfortunately the once splendid wall paintings are heavily damaged.

While Middle Kingdom society has been described as anything from a police state to a totalitarian or prescriptive society, Grajetzki rejects these terms as not very useful. The ruling class was heavily interconnected through family ties, while a middle class is difficult to identify in the archaeological or written record. It is clear that the central government actively tried to bring all parts of the population under state control. At Wadjet, most burials of the wider population for this period are missing.

For the Second Intermediate Period (1750-1550 BC), settlement remains at Wadjet are missing. Local courts and cemeteries became poorer as Thebes grew in power. After 1550 BC, a ‘history from below’ for the Wadjet province becomes impossible to write.

Concluding remarks

One of Grajetzki’s conclusions is that regional data is often lacking in modern archaeology, as focus is put on the recording and protection of single sites. His is a noble endeavor, trying to piece together the social history of a rural, provincial area, often with additional information about similar places during the same period. He paints an intriguing picture, well illustrated with find material, and touches upon interesting theoretical points, although I am not always in agreement. It seems the book was written with a wider audience in mind (in the spirit of the subject matter itself), although many details are probably still too technical for non-Egyptologists.

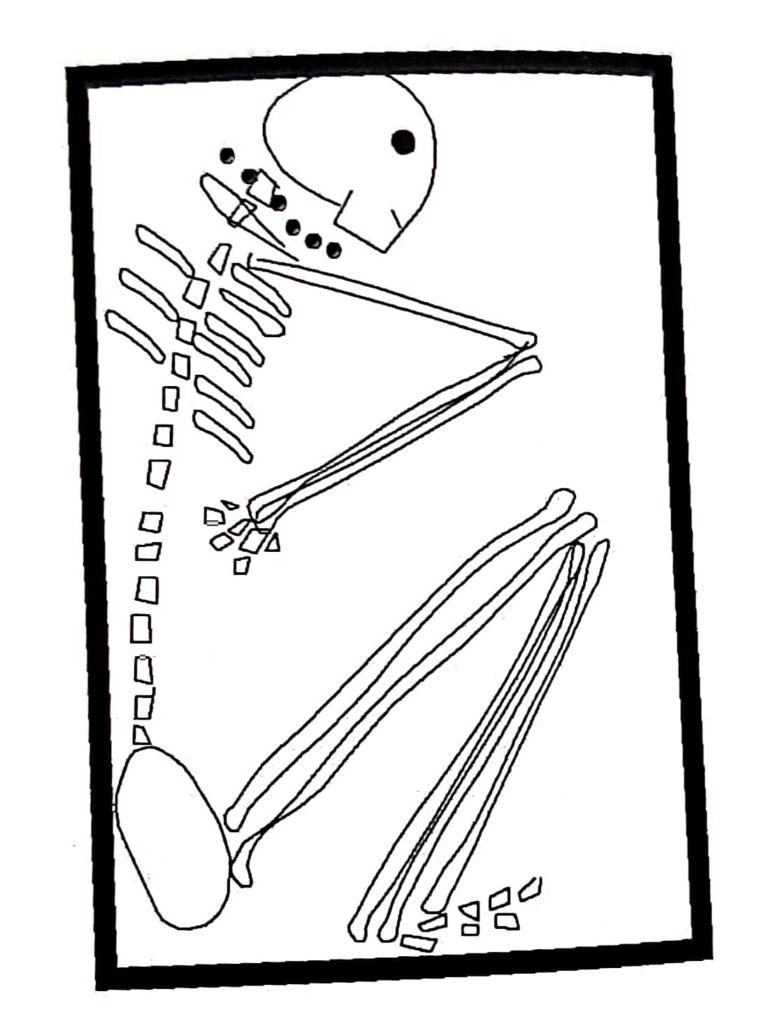

Some maps lacked a scale and/or north arrow (e.g. fig. 6) and a scale would perhaps have been useful on archaeological (pottery/find) drawings as well (e.g. figs. 7-9). Some images appear pixelated (figs. 40-42). Drawings of skeletal remains (figs. 55-59) are endearing.

Burial 7795 of a child or young adult (fig. 55)

With

With