After three delightful popular books about entrepreneurs in ancient Egypt (two of which were female, see reviews here and here), Koen Donker van Heel is back with a fourth installment in the series.

After three delightful popular books about entrepreneurs in ancient Egypt (two of which were female, see reviews here and here), Koen Donker van Heel is back with a fourth installment in the series.

Dealing with the Dead in ancient Egypt: The Funerary Business of Petebaste (AUC Press) is about a mortuary priest (choachyte) living in 7th century BCE Thebes. Simultaneously, the author has published a scientific edition of the 2700 year old papyrus archive.

The reason why Donker van Heel is mad publishing two books side by side is to reach a wider audience with a subject as notoriously niche as abnormal hieratic. In this popular version, he can pour out his ‘wild ideas and speculations’ (his words), along with snide remarks such as these:

“An Egyptologist needs to have full mastery of English, French, and German, and otherwise turn to something less taxing, such as Amarna pottery.” (p. 18)

…is something Radcliffe Emerson could have said in the Amelia Peabody series.

The complexity of the subject matter becomes clear right from the start. Competing chronologies, seemingly unnecessary relabeling of scraps of papyrus, and a history of generally brilliant but sometimes petty demotists (not to be confused with demonists) – as the scholars of this highly cursive business script are called.

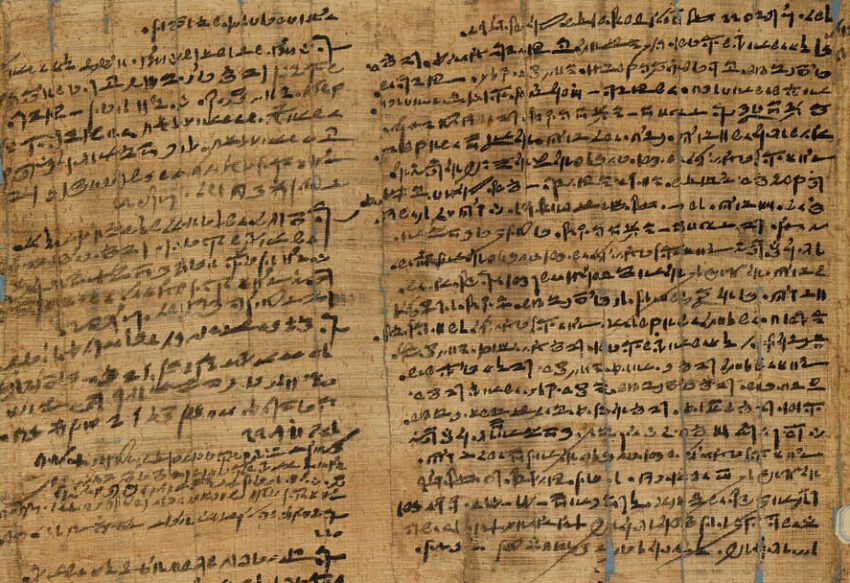

Essentially, eight papyri now kept in the Louvre and written in what is lovingly termed ‘abnormal hieratic’ deal with the business archive of a Theban mortuary priest, the choachyte or water-pourer Petebaste (“Whom (the cat goddess) Bastet has given”). They were found together on the west bank of the Nile near Luxor and sold to antiquities dealer Giovanni d’Anastasi, who also happily filled the stores of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden.

The papyrus documents entered the Louvre collection in 1857, where they were first studied by Théodule Devéria. At the same time, the Germans were making large strides compiling a grammar (as they tend to do) of the elusive demotic script. Welsh Egyptologist Francis Llewellyn Griffith only realized in 1909 that the Egyptians of the seventh century BCE actually used two scripts for their administration: demotic in the north and abnormal hieratic in the south. These survived side by side until demotic won the arms race around the time of king Amasis (570-526 BCE).

Petebaste

So what do we know about our hero Petebaste? In fact, next to nothing, if it weren’t for P. Louvre E 3228 A–H (docs. 1–8). His father was called Peteamunip, but that was a generic name at the time. Petebaste would have been born around 725 BCE, and lived up to fourty years, which was a ripe old age in ancient Egypt. He probably worked at Medinet Habu at some point. Choachytes like Petebaste were charged with providing water offerings to their deceased clients, for which they were paid in aruras of (fertile) land, but whether they owned the land or just its crop yield is unclear.

Six of the eight texts in Petebaste’s archive mention a single family of clients, among whose ranks two choachytes are found: Setjaamungu and his granddaughter Hetepese II. The job was hereditary, and could also be held by women. A useful family tree can be found on p. 31. It is interesting to glean from the texts that the ancient Egyptians were as concerned with the division, sale, inheritance and contesting of property as modern day families. Intriguing is the sale/lease of people and/or their labor, a practice we already find in New Kingdom Deir el-Medina, where servant women were rented out to bake bread.

After introducing the archival texts, Donker van Heel goes on to explain why hieratic is so abnormal. The two scribal traditions diverged after the empire had fallen apart in two halves after the New Kingdom. The southern script grew organically from the hieratic script used in the Ramesside administration. A kinder term for abnormal hieratic would be ‘late cursive hieratic’, but hieratic of itself is already rather cursive. When king Psamtik I reunified the land in 656 BCE, administrative reforms led to the ditching of abnormal hieratic, favoring the northern demotic script as being more standardized and precise. The fact that one sign in abnormal hieratic could denote a range of different hieroglyphs (or the same word could be written with a variety of signs) did not add to its clarity and workability in court.

Petebaste lived during the time of Montemhat, owner of one of the largest Theban tombs (TT 34) located in the Asasif necropolis, opposite Deir el-Bahari. Montemhat carried such titles as fourth prophet of Amun, mayor of Thebes and governor of Upper Egypt. He married powerful women to elevate his status while a power struggle was going on between the 25th Kushite dynasty and the 26th dynasty of Psamtik I. Montemhat was a power broker who orchestrated the installment of Psamtik’s daughter Nitocris as god’s wife of Amun in Thebes, coming from the north and bringing many donations to the temple of Karnak. Upon arrival in Thebes she was adopted by her predecessor, the Kushite lady Shepenupet II, as detailed in the Nitocris Adoption Stela:

Regnal year 9, first month of akhet, day 28. Leaving the king’s private apartments by his eldest daughter dressed in fine linen and adorned with new turquoise. She had many attendants with her, and magistrates cleared her way. They went in great spirits to the quay to go south to the Theban nome.

The archive

One of the papyri (doc. 3) in the archive deals with the division of a house, including apparently a sycamore tree and the use of its floor. This calls to mind the cultural peculiarities of renting an apartment in the Netherlands vs. Germany: one without floors, the other without a kitchen, both being rather essential elements of a house. That land and property was of concern to the ancient Egyptians is clear. A case described in P. Mattha easily invokes the petty disputes handled in the Dutch TV show ‘De Rijdende Rechter’:

If a man obstructs a house to prevent it from being built, and if he says: “Builder, do not build,” and he (the builder) builds, and if he (the man who filed suit) complains to the officer of police, saying: “I said to the builder: ‘Do not do construction work on the house,’ and he did not listen to me, so he built illegally,” the builder will be questioned.

The choachytes were furthermore organized in associations with fraternity-like mores (no sleeping around), but who also cared for each other in the event of a death in the family. (This mostly involved drinking with the bereaved).

The book inevitably turns to legal history. Messy divorces and squabbling over inheritances were as much a part of the past as they exist in the present. When a dispute went on for too long it was eventually assigned to the Great Court of the capital city Memphis. Quarrels over land and crops were high on the list. Court documents were appended with a list of witnesses and oaths were taken on penalty of corporal punishment and a one-way ticket to wretched Kush (a threat rarely acted upon). If you were particularly pleased with the result of a court proceedings, you could opt to have the text drawn up in your tomb chapel for posterity.

In the case of a loan (doc. 6), the document drawn up would remain in the possession of the lender until the full sum was repaid. Our man Petebaste borrowed grain (measured in khar) against the steep interest rate of 50 percent, but could actually still make a nice profit. Furthermore, there was a 10 percent harvest tax to be paid to the royal or temple domain where the field was located.

In the end, our enterprising choachyte dealt with caring for the dead. Doc. 7 and 8 in the archive concern the embalming of a Mrs. Taperet. The place of mummification (‘the Good House’, cool name for a Netflix series) needed to be readily stocked with linen and resin. Mummification was a sticky business. Singers were involved, to be paid in beer and black eye paint. Sycamore wood and red pigment were required, and the scribe to be provided with milk. These lists of items are especially intriguing. What is clear is that specific rituals were enacted on the last night before the burial, possibly costing up to 6 deben.

All in all, Dealing with the dead provides an insightful peek into an often overlooked period of Egyptian history, decoded using an impossible script, against the backdrop of the sometimes inimitable workings of Egyptology. There are certainly merits in looking at texts from an archival perspective (and writing funny little books about it). Abnormal hieratic is not for the meek, but Donker van Heel manages to enlighten and entertain us without the need to follow a two year long graduate course. For those nevertheless interested: Demotic 1-3 and Abnormal Hieratic at Leiden University. Ask for Koen!

Things I’ve learned:

-

Two aruras of land are the size of a soccer field (next book: did the ancient Egyptians play soccer?).

-

Demotic and abnormal hieratic can be likened to WWII fighter planes (I want to refer to a page number but the publisher only sent me a lousy protected pdf that self-destructed after reading).

-

The Egyptian language is still ripe with hapax legomena: words occurring only once, so you have to guess their meaning based on the context.

-

So far, no legal document from the 25th or 26th dynasty has been found that was signed by a female witness.

-

We should not look at ancient Egyptian law from the constricted framework of Roman law, but regard it in its own right.

-

Abnormal hieratic (and in extenso, Egyptology) should be studied in cooperation with other researchers for the best possible outcome. Hear, hear.

-

The joy of reading abnormal hieratic is to end up with more questions than you started with.

1 thought on “Bring the abnormal back in hieratic”