In the fall of 2019 (BC: Before Covid) I packed my bags and my mum to spend one month in sunny Luxor. Staying in a flat on the rural west bank of the Nile, I planned to relax, work on a PhD proposal and take lots of photographs. With the assistance of Julia Thorne from Tetisheri and a friendly employee at the camera store, I had selected the camera that would suit my needs: the Sony α7 II with standard kit lens (my budget had run out at that point).

I can’t say I’m a good photographer. But what matters most – like with any creative pursuit – is that I thoroughly enjoy it. As a child, I would photograph the beaches, dunes and pine forests of North Holland. Visiting Egypt, Greece and Rome as a teenager, I would take endless photos of sand coloured temples against a backdrop of clear blue skies. Also, lots of blurry photos of objects in museums where no flash was allowed and the glass cases reflected the light, such as Tutankhamun’s treasures in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Ram-headed sphinxes leading up to Karnak temple.

From my first student salary I bought a Canon EOS 400D, a 10 megapixel DSLR camera that surely had its shortcomings, but fitted right within my budget. I was too afraid to bring it on an excavation to Germany at first, but then took it on a three-month trip to Egypt later that year. It was especially good at capturing pyramids basking in sunlight, dusty Cairo streets, desert environments and people (when I dared to take the liberty to photograph them). It functioned less well inside dark tombs and museums, where I had to crank up the ISO and keep the camera very steady, a thing I learned to do well.

After 11 years of faithful service, when camera phones started getting better than my by now antique camera, I decided it was time for a new baby. Due to a fortunate tax return I had some cash to burn. But where to start? I was used to a Canon, so it would seem reasonable to choose a newer model in the same line (800D) or up the game and go semi-pro (6D Mark II). This is where I started asking advice from Julia, whose posts I had seen on Twitter.

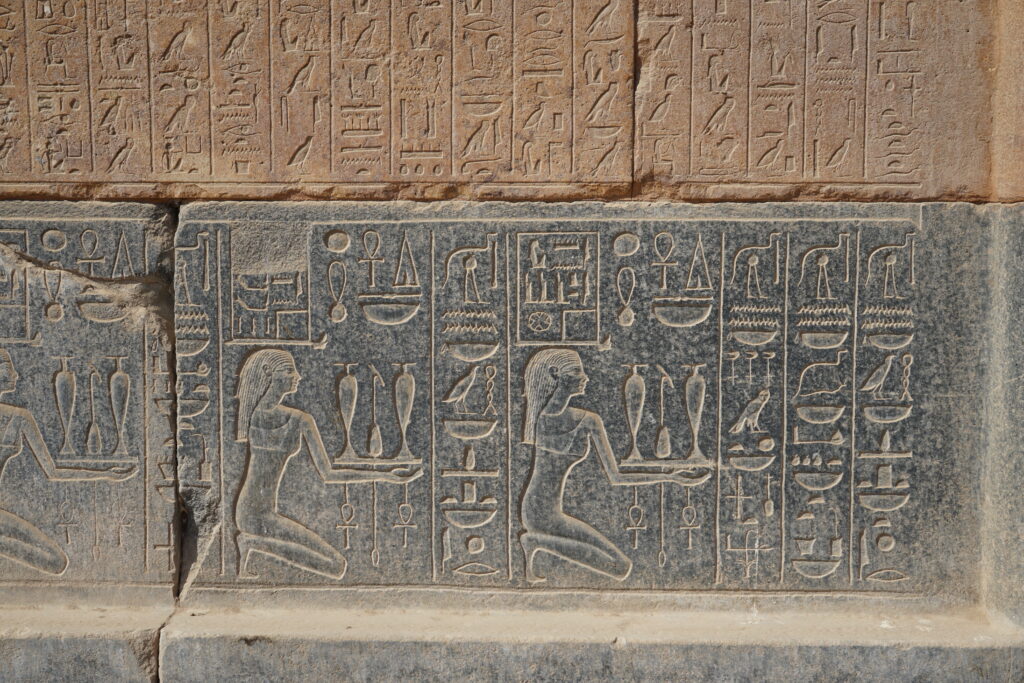

Relief of the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut in the Karnak Open Air Museum.

Julia convinced me to go mirrorless, as these cameras can do much the same as chunky DSLRs, while being lighter and more compact for use inside tombs. On all accounts, a new camera would be much better at dealing with low light, which was exactly what suited my photographic wishes. At one point I was eyeballing the Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II.

Something that had always been a problem in Egypt was the restriction on taking photographs inside tombs and enclosed spaces. No doubt stemming from concerns about the use of flash in the old days, and turned into a handy way of earning bakshish (tips) when the gafirs (guards) turned a blind eye. Nowadays, photo tickets can be acquired for non-commercial use costing 300 Egyptian pounds (about 15 euros), allowing for photography in three tombs per site. Also, non-commercial photography inside museums is allowed for a small fee with an official ticket. As most people now own a smartphone, the use of camera phones was even allowed for free.

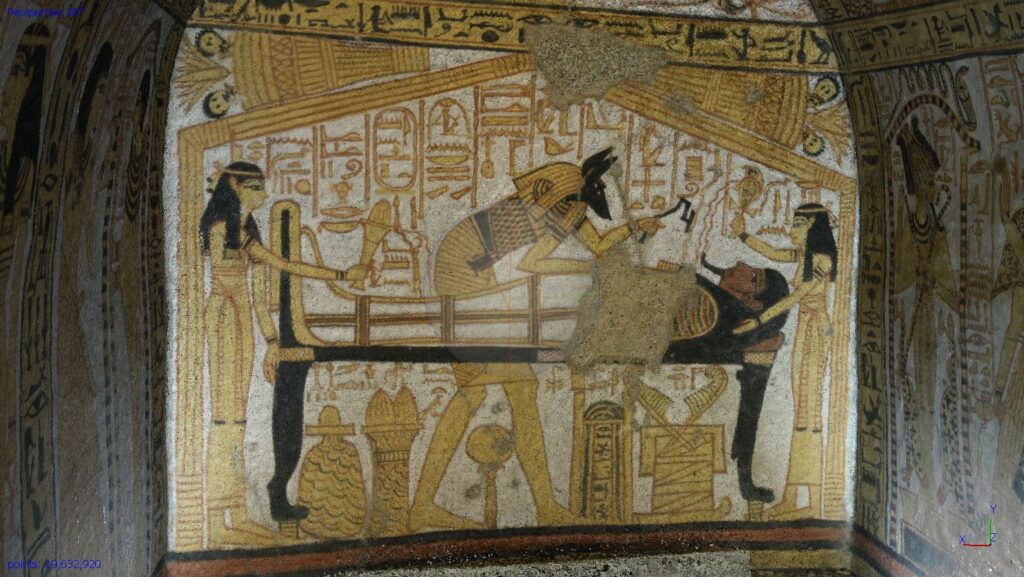

Inside the tomb of Amennakht (TT 218) at Deir el-Medina.

The time was ripe to buy a new camera and I ended up with the Sony α7 II, a full-frame mirrorless camera that is compact and can also shoot film. A prime (fixed focal) lens would have been useful for photographing tomb scenes, but I wanted to use it for a variety of purposes (including a lot of landscapes) so I stuck with the standard kit lens to begin with. The downside of using multiple lenses in Egypt is that switching them around can cause tiny dust particles to get lodged inside the lenses and camera body.

I also use photogrammetry software to stitch together a large number of overlapping photos to create 3D models. For this, a prime lens would actually be helpful because of its fixed focal length. The photogrammetry software finds overlapping points in each of the photos, thus building a point cloud that can be extrapolated and turned into a 3D mesh with overlying texture.

Point cloud generated from photos taken in the tomb of Nakhtamon.

As I’ve mentioned, I am not a pro and purely engage in photography as a hobby. I have a basic understanding of shutter speed, aperture and ISO. I know I need to be photographing in RAW and processing in Lightroom, and that I should buy a tripod. The thing is that I want to keep things as low maintenance as possible, not lug around too much equipment and get into arguments with the guards for more bakshish. However, as I am now doing a PhD project on tomb iconography that eventually needs to be published, I will probably need to up my game and become a bit more professional.

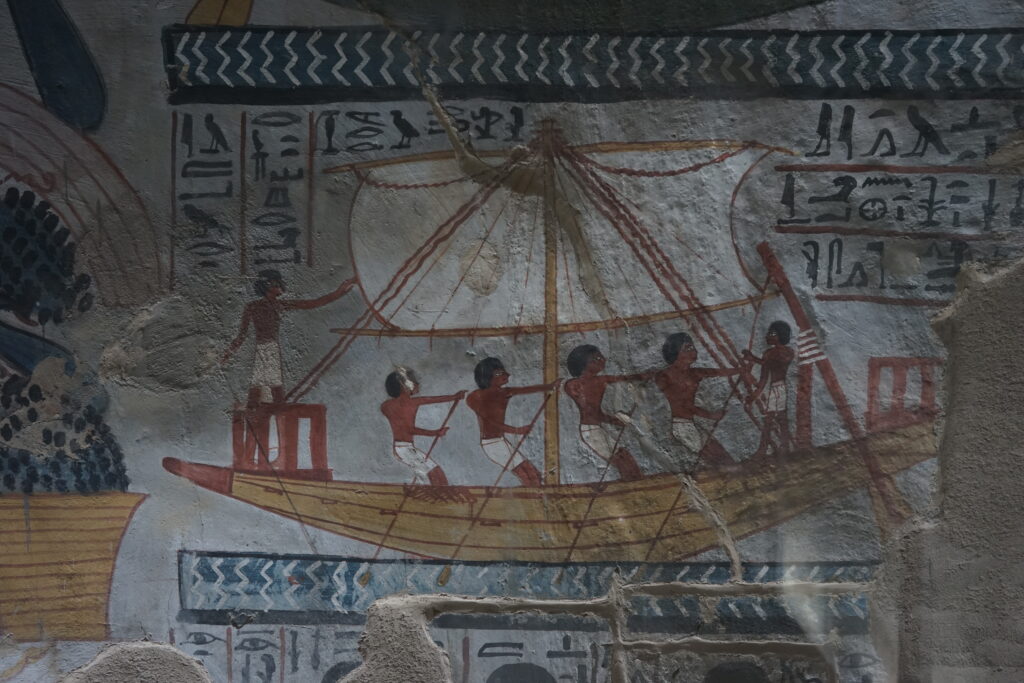

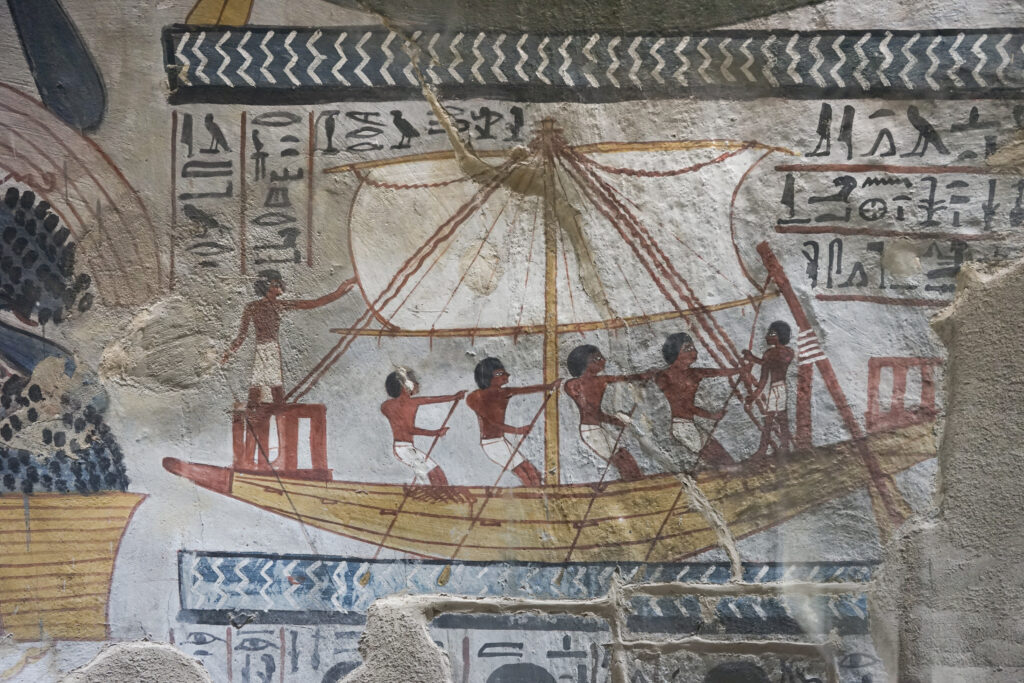

In practice, I found the photos I took with my new camera to be much clearer and brighter than with my previous camera. In tombs and dark areas the photos still turned out quite dark, trying to get the F-stop (aperture) as high as possible without the image becoming blurry (from a hand-held position). In the following example, Julia worked in Camera RAW to up the exposure, add texture, as well as use the adjustment brush to bring the exposure up around the darker, upper part of the photo I took.

Boat in the tomb of Sennefer, before and after edits.

A problem in Egyptian tombs is still the reflective glass and uneven, fluorescent lighting. Inside tombs, it is best to take multiple photos using different shutter speeds, as well as increasing the ISO. Stand steady with feet apart, arms clamped to your sides. There are also stabilizers on the market, but like tripods, these could cause trouble when used inside small tombs. Be careful with (automated) noise reduction, as this can smudge the photo while you would rather keep the detail, even if it means there are some grainy bits.

All in all, the new Sony camera has already brought me a lot of joy. Current events intervened, but I will be happily taking it with me on my next journey to Egypt.

Statue of Sakhmet at Medinet Habu.

Ik vind die foto’s prachtig!