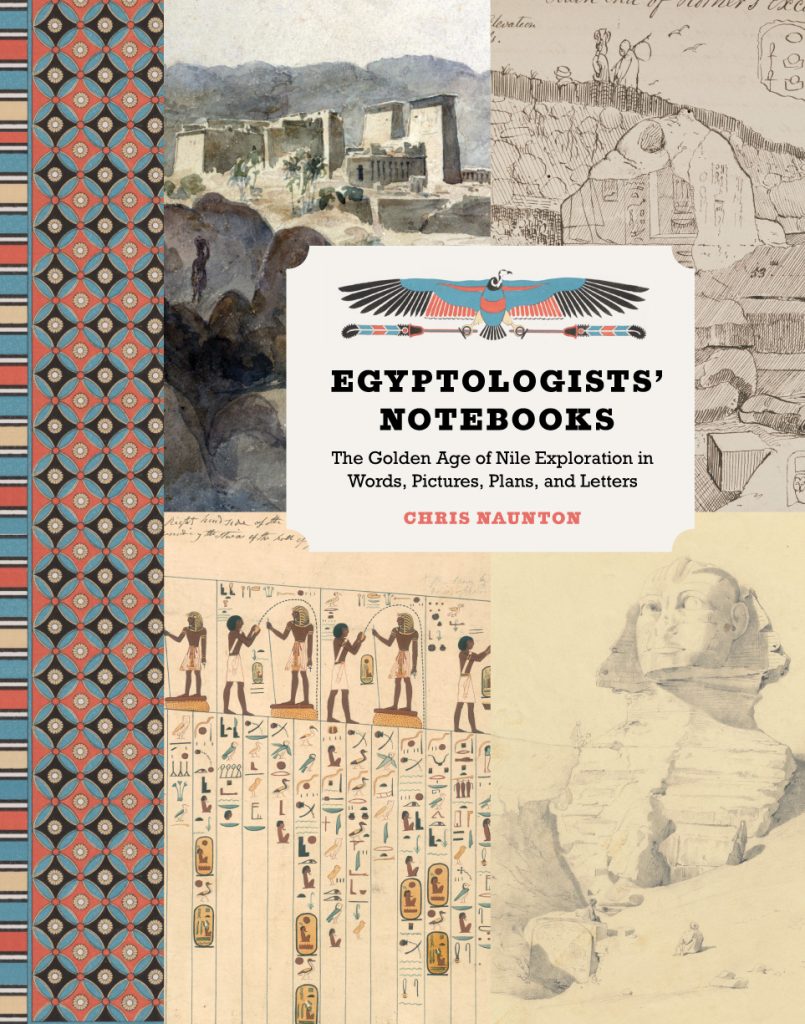

Egyptologists’ Notebooks (2020)

Egyptologists’ Notebooks (2020)

Chris Naunton

Thames & Hudson

264 pages, 242 ill.

ISBN: 9780500295298

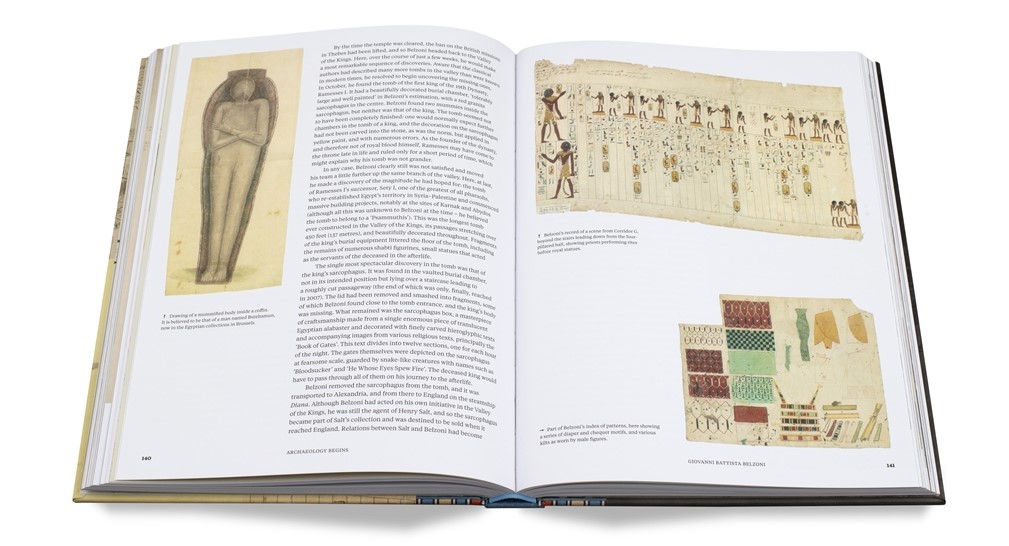

To be fair, the reason I wanted to review this book was simply to have it in my possession. It being a gorgeous bound and embossed volume with matte paper that beautifully brings out the 242 sketches, maps, plans, watercolours, facsimiles, notebook pages and photographs that form the core of its appeal. In five sections, 32 short biographies are given of (as history would have it, predominantly white male) explorers and Egyptologists. Each richly illustrated with their own works and that of their team members (and wives).

It is true that these early travellers painted Egypt in a soft, romantic, orientalist light, while shamelessly bartering for antiquities, breaking into caves full of mummies and cursing the ‘wretched people of Qurna’, afterwards sipping lemonade in the breeze on their dahabiya. But this volume also points to the wealth of information and artistry that archives still contain, slowly being unlocked by digitisation efforts. See for example the wonderful Sura Project, that aims to make available the photographic archives of the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels.

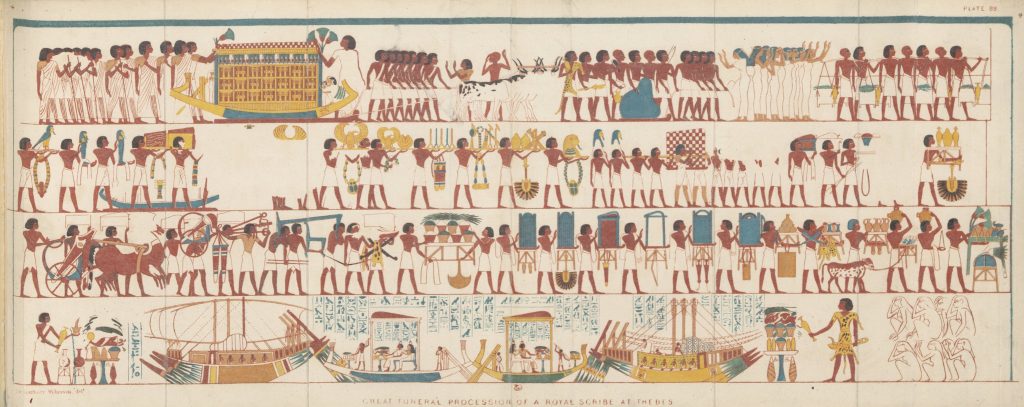

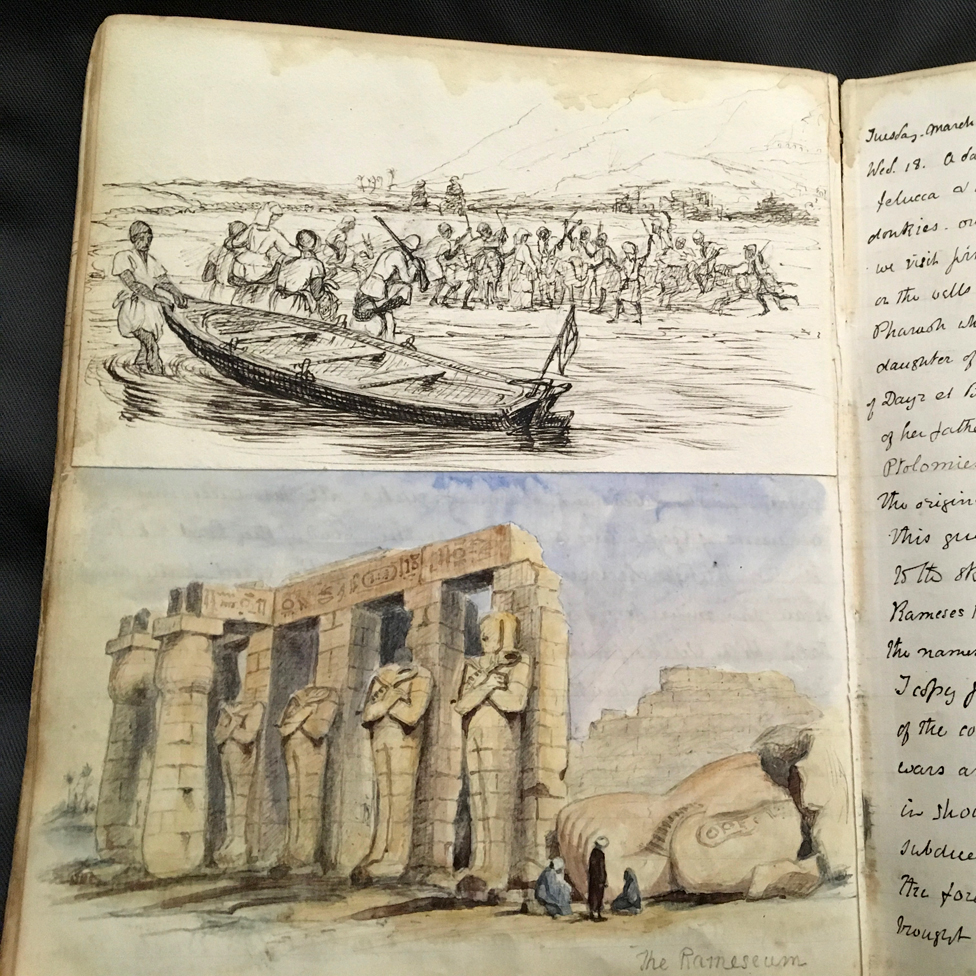

Our early Egyptologists did not have photography to resort to, but used tracing paper and pencil, ink and paper, compasses and watercolours to record their finds. The artistry that went into these drawings is remarkable, and a lost art for most Egyptologists today (although retained in the skill of epigraphy, pottery drawing and the recording of small finds). I personally cannot draw for the life of me, although digital drawing tablets help to remedy that fact. The accuracy of maps that were made before the era of Total Stations generally astounds me (see for example Howard Carter’s map of the Valley of the Kings on p. 210).

What is still current today is the eye for detail, the need to record the progress of an excavation minutely, lest you forget, and to publish accurately but swiftly. It is a pity that a chapter could not be devoted to Auguste Mariette (although he is featured in the intermezzos on p. 134-135 and p. 170-171), simply because he failed to publish and had much of his notes destroyed in a flash flood that ravaged the Egyptian Museum then located in Bulaq.

The story of Egyptology inevitably begins with the ‘discovery’ of the country by Europeans, often clergy or military men (but cf. El Daly’s Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. Ancient Egypt In Medieval Arabic Writings, 2005). We hardly recognize the un-Egyptian colossi, pointy pyramids and strange renderings of the landscape such as Pococke’s map of the Valley of the Kings. There was no feel yet for the Egyptian style of representing, or indeed for the meaning of the hieroglyphs. In fact Egypt was approached as just another ‘antique land’, not a nation in its own right. Dominique Vivant Denon, member of Napoleon’s scientific entourage, first captured something of the monumentality of the temples, craftsmanship of the sculptures and indeed the ‘orientalist feel’ that would attract later travellers.

‘Family of Egyptian Fellahin, at Tomb Entrance’ (Vivant Denon)

We see the heroic feats of male Egyptologists, climbing into the Great Pyramid and descending into the hot hell of the sand-filled temple of Abu Simbel, but what we tend to miss are the daily adventures of their female counterparts. Edwards William Lane (p. 82-87) had a sister, Sophia Lane Poole, who visited the harems of Cairo (The Englishwoman in Egypt: Letters from Cairo, 1844). Lucie Duff Gordon was a British lady exiled to Luxor for health reasons, becoming a member of the community and writing letters home about her exploits (Letters From Egypt, 1865). These were not Egyptologists, they were not ‘on a mission’, but we can learn a great deal from them about what life was like during that time, perhaps even allowing for a more intimate, detailed look.

Living as an Egyptologist in Egypt during the 19th century was certainly adventurous: Robert Hay lived inside a tomb while mapping the Theban necropolis. Like the famous Nile explorer Samuel Baker, he married a girl he had purchased himself on the slave market. John Gardner Wilkinson built a house for himself in the tomb of Amethu called Ahmose (TT83 at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna). It lay not far from that of Giovanni d’Athanasi, agent of Henry Salt, who used decorated coffins as doors and mummy cases as fuel (wood was in short supply). Many things were permitted in Egypt that were surely frowned upon back in good old England (or France), which must have been part of the appeal of living there.

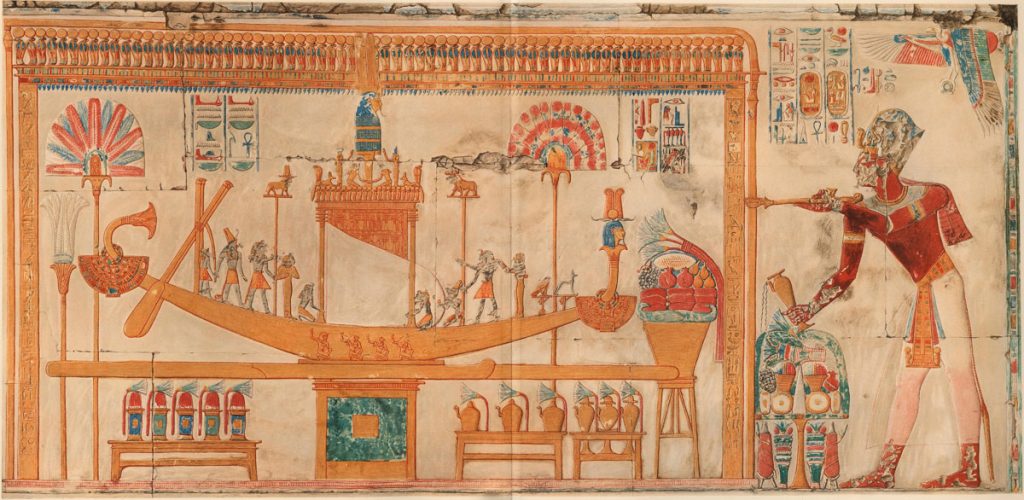

Theban tomb scene from Wilkinson’s Manners and Customs (1837)

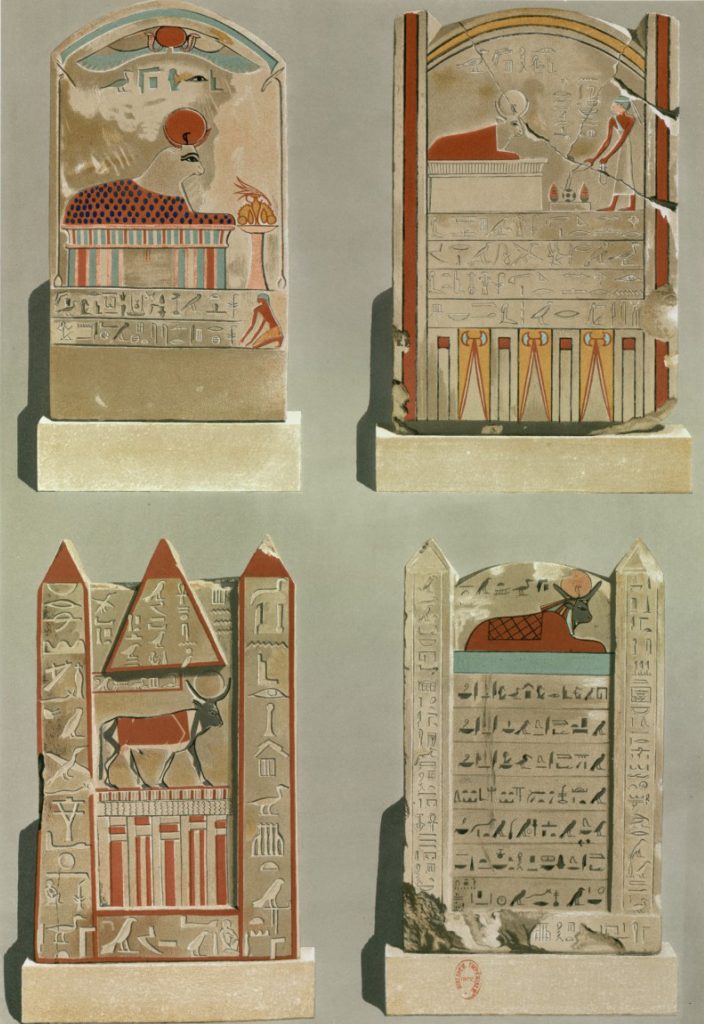

With the decipherment of the hieroglyphic script by Champollion in the 1820’s, a new era of academic interest had begun. The writing on the wall could now (at least partly) be read, artfully brought home in the elegant drawings and reconstructions by Nestor L’Hôte. Prussian scholar Karl Richard Lepsius undertook an expedition to record (and extract some of) the ancient Egyptian monuments, and published a series of volumes (the Denkmäler) that is still in use by Egyptologists today, as some of the scenes have in the meantime become damaged. Along with this academic interest came a sense of colonial pompousness: European museums vied for monuments in an archaeological arms race, sending consuls, collectors and circus strongmen to rid Egypt of its loose-lying stones. So much so that an Antiquities Service needed to be established in order to protect the monuments in situ from the grasp of looters and/or museum directors.

Thankfully, there was also attention for small finds (Rifaud’s coloured glass sherds, p. 147) and stratigraphy (Hekekyan’s gorgeous soil sections, p. 151 and central flap). Finally on p. 172 there is room for a woman, that is the inimitable Amelia Edwards. With time and money on her hands (she was a mystery writer), she visited the land of the Nile in style on a dahabiya (two-masted sailing houseboat), writing an immensely popular memoir with irony, wit and a dash of orientalism (A thousand miles up the Nile, 1877). Afterwards, she went on to found (and fund) the Egypt Exploration Fund, the archives of which provided so many of the treasures found in Naunton’s book. Because in the end, funding is what an archaeologist needs and craves more than anything to fuel their passion and live for another season.

Funding is what fueled the work of Petrie, who went around Egypt like an archaeological madman together with his equally archaeological wife, Hila Urlin. Together they put prehistoric Egypt on the map, producing books chockfull of pottery drawings and the first paper database of archaeological finds. Next we encounter another British lady (or actually two): Marianne Brocklehurst, who with her ‘companion’ Mary Booth (they were buried together) travelled to Egypt, funded excavation, witnessed the extraction of the Deir el-Bahari cachette and charmingly illustrated her travelogue to boot.

Illustrated diary of Marianne Brocklehurst

Facsimiles and artwork that capture the spirit of Egyptian art we owe to Percy Newberry (although unfortunately much reduced in size for publication), Rosalind Paget (a new name!), Howard Carter, and the power couple Norman and Nina de Garis Davies (co-publishing under the name ‘N. de Garis Davies’). Finally, photography was going to replace drawing in situ (but cf. the Epigraphic Survey of the Oriental Institute in Chicago) and still later, 3D models based on photogrammetry. Still, everyone should try their hand at a spot of finds drawing from time to time.

Only one Egyptian name is present in the book: Hassan Effendi Hosni. It is an oversight of history that so little Egyptian archaeologists received the chance to practice their art, and that so little of it was published. Hopefully, Egyptian Egyptologists of today will scour their archives (such as the Abydos Temple Paper Archive) and bring to light the stories of those that came before us, to gain a more complete picture of the past and create a more solid base for the future. I would here like to mention Jill Kamil’s biography of Labib Habachi: The Life and Legacy of an Egyptologist (2007), and Wafaa el Saddik’s memoir Protecting Pharaoh’s Treasures: My Life in Egyptology (2017).

Calverley and Broome, The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos (1933)

All in all Egyptologists’ Notebooks is a precious tome, especially for those interested in the art of drawing and the history of (early) Egyptology. Sometimes the order of the biographies is odd, with Belzoni coming after Lepsius and Mariette. Missing where Amice Calverley and Myrtle Florence Broome, who worked in the temple of Seti I at Abydos and produced some amazing artwork. Recently, a biography has appeared about the latter by Lee Young (An artist in Abydos: The Life and Letters of Myrtle Broome, 2021).

For those of you who can’t get enough: Naunton has extensively lectured about his book that was undoubtedly a work of love. Those videos can be found on his channel. Enjoy!

Hard to judge Egyptologist from a century ago by today’s values.

Also, don’t forget it was these same European Egyptologist who saved ancient Egypt for us today.

When I ordered this book from Amazon, I grumbled about the fact I couldn’t have it in digital form. Once I had my hands on it of course, I realised why this book could never be digital. Quite apart from its content, this book is simply a joy to touch, to feel the textures and the weight. As I think I have said elsewhere, this is a book you will read cover to cover, but will never finish.