It was a hot day for a funeral. The local cemetery was basking in sunlight. The family was sat inside, socially distanced, with the open coffin in front. A grandchild stood up to speak, “Goddamn it, grandma,” began the speech. I was not a part of this. It was not my family. I sat outside on a bench beneath a tree, awaiting the end of the service. Finally the family exited the brooding hall, taking positions to accompany the coffin to its final resting place – a newly dug grave in a barren part of the cemetery. The trees did not yet have a chance to grow, but out of experience I knew they would. (I had excavated a graveyard – disentangling plant roots from skulls and vertebrae – it was like gardening, really).

There was mum, earnest, alive. I took her hand and we followed the procession, a black-clad clan, up the hill and to the burial site. We were the last to throw our roses in the pit. (How do they make those profiles so sharp? There was a special digging machine lying to the side). “I’ll go to the market without you then, sis,” mum said to the coffin. Sis. Sister-in-law. The nearest thing to a sister she had? They had known each other for 45 years, from their adolescence in Amsterdam, with periods of envy and friendship ending in six years of silence. The ceremony was over, so we went to eat cake. Proper cake, not the soggy stuff they serve at funerals. Who knew it would be one of the last times I ate cake with my mum.

Luxor, Egypt

The balloon had most definitely strayed out of course. Due to a strong wind blowing from the west we had crossed the river, over Luxor Temple and the cruiseboats moared along the Nile, their blue swimming pools encased in green lawns. Over the Winter Palace Hotel and its gardens, the corniche empty at this time of day. Over the train station and rows of concrete housing blocks, towards the mountains in the east, the sun rising swiftly. Over fields of green (clover and sugarcane) when we heard a wailing in the distance. Below us, ants were crawling, not ants but black-clad women, walking up and down a street and howling. It was a funeral.

Wailing women as seen from the hot air balloon

What a relief would it be to audibly vent one’s grief, to not bottle it up and put it away for times of quiet despair. Although strictly speaking forbidden at Islamic funerals (I’m not an expert), distracting from an otherwise solemn occasion, it seems to be present in a variety of cultures (again, I’m not an expert), from Greek klauthmós to Irish keening. In the distance behind us, the western mountains where ancient Thebans buried their dead, below us, the eerie sound of communal grief.

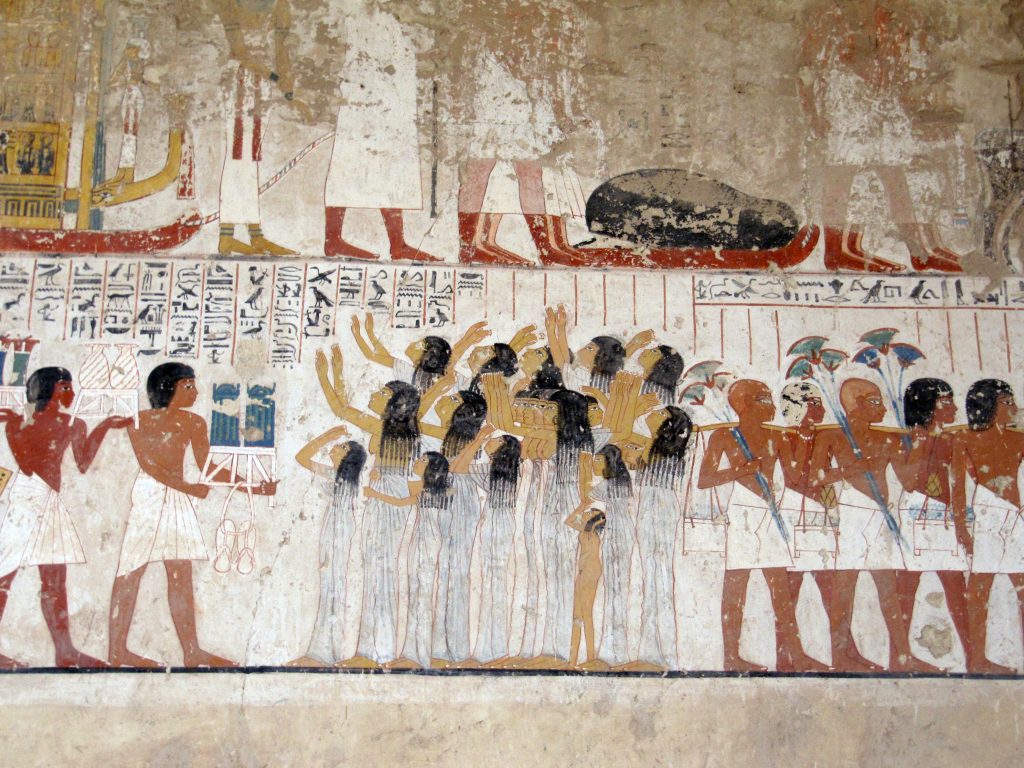

In the tomb of Ramose at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, a necropolis of the ancient Egyptian elite on the west bank of Luxor, a sequence is depicted showing the (imagined) funeral of the tomb owner. In two registers, a procession of people and objects (lots of objects) is shown accompanying Ramose to his final resting place in the Theban hills. His sarcophagus is towed on a sled, family members are carrying flowers, furniture is hauled as if Ramose is moving house and rows of officials close the lines. A group of women clad in linen, bare-breasted and with loose hair, are depicted in motion, arms heaved up and tears running down their face. No doubt these women, both young and mature but all beautiful, would have made some noise.

Professional mourners in the tomb of Ramose

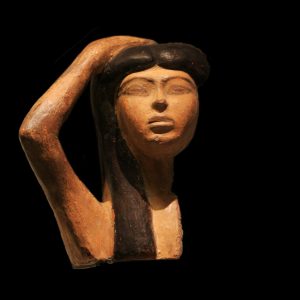

This scene is repeated in several tombs. The women are almost certainly professionals, paid mourners ultimately impersonating the godessess Isis and Nephtys grieving for their mythological husband/brother Osiris. A painted statuette in the Louvre (E27247) depicts the same posture in 3D: hand held up to the head, loose hair and a pained expression.

Statue of a mourner/Isis (Louvre)

As an Egyptolgist I study dead things. Tombs, mummies, statues and objects that were meant to last for eternity. The stuff of daily life was made of perishable materials, long since washed away by the Nile (with its shifting branches and slow, eastward wanderings) or reduced to a discoloration in the mud. Thanks to the hieroglyphs carved in stone we still know the names of the dead, their deeds and their boasting.

As an Egyptologist I study death and yet death is not something I had ever wrapped my head around.

In rural Luxor a car with loudspeaker announces the recent dead. ‘Bismillah ar-rahman ar-raheem’, followed by the name and affiliation of the deceased, over and over again. A tent of colourful cloth is set up at the house of the family, where for three days they sit and receive guests with tea, while being fed by the community. Within 24 hours, the deceased must be buried in a plain white shroud, in a shallow grave in the desert without frills.

Grief is just another word for love. Love that has nowhere to go, no one to receive it. It is an undirected cry aimed at the sky, like the wailing of the women in Luxor.

My mother died on 20-10-2020. What a date. Mere months after the death of her sister-in-law there was to be another funeral. Needless to say it broke my world.

I revisited Egypt a year later, in October 2021. For the first time in nearly a decade I was without her company. It felt like I had to bring the news of her death to Luxor, to talk to the people she knew, to visit the places she loved, to find her there.

“It is life,” one person told me. “We will see her again,” offered another, and promptly it started raining in the desert. A third person just made me tea. And on the last morning, when the taxi driver we both knew brought me to the airport, and we drove again towards the western mountains, with hot air balloons rising over the plains, and I started crying audibly in the back of the car, Ashraf spoke softly: “I think you loved your mother very much.”

Yes, very much.

Looking west from a hot air balloon above the east bank

Beautifully written.

“Grief is just another word for love. Love that has nowhere to go, no one to receive it. It is an undirected cry aimed at the sky” ……. such a lovely description.

Thank you for sharing. Carolyn.

Wat een prachtig verhaal!