In the cemetery of Vienna stands a tall black tombstone with the names of a Jewish family.

The German inscription reads: “Here lies Herr Jakob Stökel, born 15 May 1822, died 18 October 1897”.

The Hebrew text is a little bit more extensive: “Here lies the honorable rabbi, our teacher, Jakov Stokel, son of Alexander. Passed away on the 22th of the month of Tishrei, [Jewish] year 5655.”

Underneath it stands the name of Rosa Mohr, “the best of mothers”, who lived from 24 August 1849 until 3 March 1937 (reaching the honorable age of 87 years).

But most striking is the postscript below:

In memoriam

Dr Adolf Mohr

Elly Mohr

Herta Mohr

Died 1944 in Auschwitz

A tombstone in the Wiener Zentralfriedhof (source)

My search for Herta Mohr has brought me through archives and into Egyptological networks of the 1930s. Recently a Leiden University building was named after her in recognition of her promising Egyptological career, with all the odds stacked against her (she was young, female and from a Jewish background during the turbulent 1930s, was forced to change location multiple times and was killed during the final days of the Second World War).

Learn more about her in this podcast that I recently recorded with the Leiden University Library.

In October the new Herta Mohr building will be opened. In an attempt to find living relatives of the Mohr family, let’s dive further into her family tree.

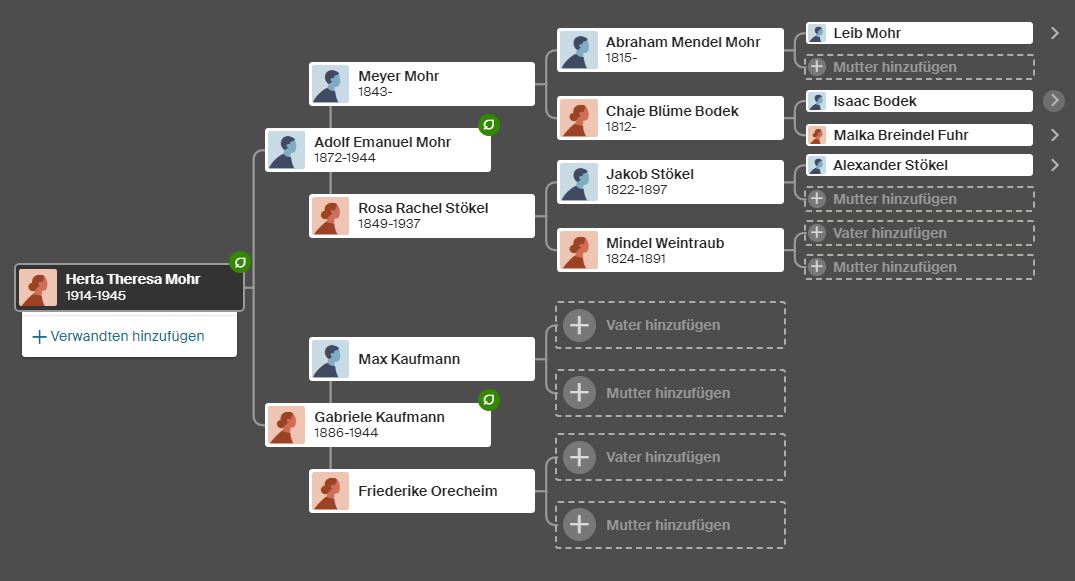

Herta Mohr was born in Vienna on 24 April 1914. Her parents were Adolf Mohr, born 1 February 1872 in Lemberg/Lviv, and Gabriele Kaufmann, born 13 january 1886 in Kaplitz. These cities were part of the Habsburg monarchy that existed until 1918. Herta had no known siblings.

Looking into Herta’s paternal family first, it seems that Rosa Mohr was her grandmother. Based on the age difference between Rosa Mohr and Jakob Stökel it seems that she was his daughter. This turns out to be the case.

In a private family tree I stumbled upon a Ruchel Rosa Mohr, born Stekel or Stokel. Her date of birth and death match our Rosa from the tombstone. She was married to Meyer Mohr (Herta’s paternal grandfather, born in 1843), both coming from Lemberg/Lviv in what is present-day Ukraine.

This in turn leads us to the parents of Meyer Mohr and the names of his eight siblings. His parents were Abraham Mendel Mohr (born 1815) and the wonderfully named Chaje Blüme Bodek (born 1812 in Lviv). Abraham’s father was named Leib Mohr (born around 1772, died 1846 in Lviv). Chaje Blüme’s parents are also known: Isaac Bodek and Malka Breindel Fuhr.

We now also find clarity about Rosa’s parents: Jakob Stokel and Mindel Weintraub. Rosa had 6 siblings. So rather than with her husband, Rosa was buried with her father.

Let’s turn to the family of Herta’s mother, Elly Kaufmann.

Searching the records of JewishGen, we find that Dr. Adolf Emanuel Mohr married Gabriele Königstein in the synagogue in Währing (a district of Vienna) in 1913. A year later, a daughter is born. This was Herta.

Synagogue in the Schopenhauerstraße in Währing, Vienna (source)

This leaves us to explain why Elly Kaufmann was called Königstein when she married Adolf Mohr. Elly would have been 27 when she married him. Was she married before to a Königstein?

On Geni we can find a record for Gabriele Königstein, born 13 January 1886 (the date fits) to Max Kaufmann and Friedrike Orecheim. Here she is shown maried to Hugo Markus Königstein, who was born 20 July 1877 and died aged 66 on 19 October 1943 in the ghetto of Theresienstadt. Could they have been divorced?

Herta Mohr’s family tree now looks like this (click to enlarge):

Are you or do you know descendants of these families? Then we would like to cordially invite you to the opening of the Herta Mohr building in October 2024.

Please contact me through info@nickyvandebeek.com, also if you have more information that can be of help.

I’d like to conclude with this paragraph from Vasily Grossman’s essay/short story, Eternal rest:

“Grand tombs, memorial inscriptions and the flowers that grow on a grave are all equally unable to show us the soul of someone who has died; they cannot show us their love or grief. Stone, music, prayer and the lamentations of mourners are all equally powerless to convey the mystery of the human soul. The sanctity of the soul’s holy mystery makes everything else seem contemptible. The drums and brass trumpets of the State, the wisdom of history, the stone of monuments, howls of loss, prayers or remembrance – all these seem as nothing in the presence of this mystery. So: here we are – this is death for you.”

—

Read more: Braving the odds: Egyptologist Herta Mohr during the Second World War, in: Navratilova, H., T.L. Gertzen, M. De Meyer, A. Dodson and A. Bednarski (eds), Addressing Diversity: Inclusive Histories of Egyptology (2023), 181-203.

(In this article I incorrectly wrote the names of Herta’s parents as Adolf Israel Mohr and Gabriele Sara Kaufmann. ‘Israel’ and ‘Sara’ were epithets given by the Dutch administration to mark Jewish persons. I sincerely apologize for this oversight.)

Listen to the podcast: The Tragic Fate of Egyptologist Herta Mohr

Acknowledgements: With thanks to my dear friend Jonathan Sela for the Hebrew translation of the tombstone and for recommending the JewishGen website.

I am a relative of Herta’s in The US – I just sent you an email!